Considering the sublimity of nature, time and the cosmos, Almond utilises numbers as a formal syntax to offer a structuring of time that acknowledges its inherent instability. As a basic organising system, numbers enable the scaling and mapping of space, provide the language for economics, the coding for technology and the understanding for bodies of knowledge – such as quantum cosmology – that might otherwise remain opaque. This visualising of time through physical, mechanical or celestial chronologies is variously layered by Almond’s meditative abstraction, manifesting time as an intensified phenomenon.

The notion of time as both a ‘real’ and fictional condition informs Almond’s practice, and is realised in early works such as A Real Time Piece (1996), comprising a live satellite link recording the passing of light across his empty studio over a 24-hour period. A different charting of time is present in Almond’s sculptures, which often utilise the flip clock as a recurring form – a technology that visibly and audibly registers the passage of time, most conspicuously in the liminal spaces of transport hubs. Functioning as timekeepers and sculptures, and exhibited either singularly as distinct objects or collectively as stacked formations, these assimilate the very mechanics of horology to convey time’s intractable transiency, despite its many frameworks.

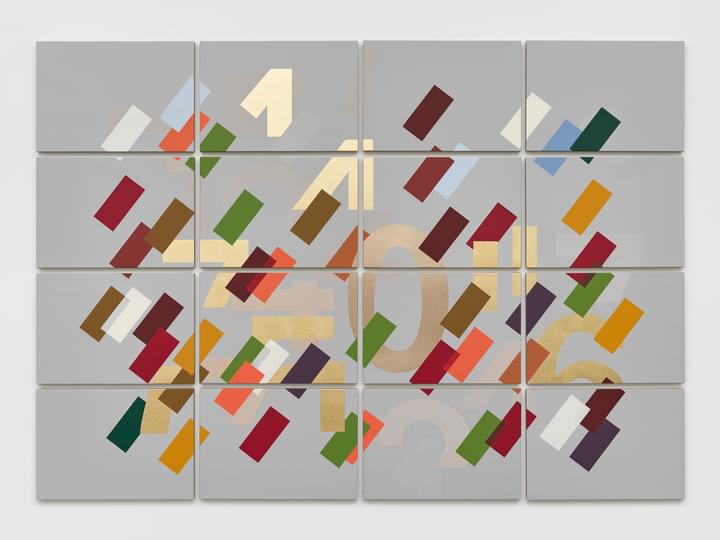

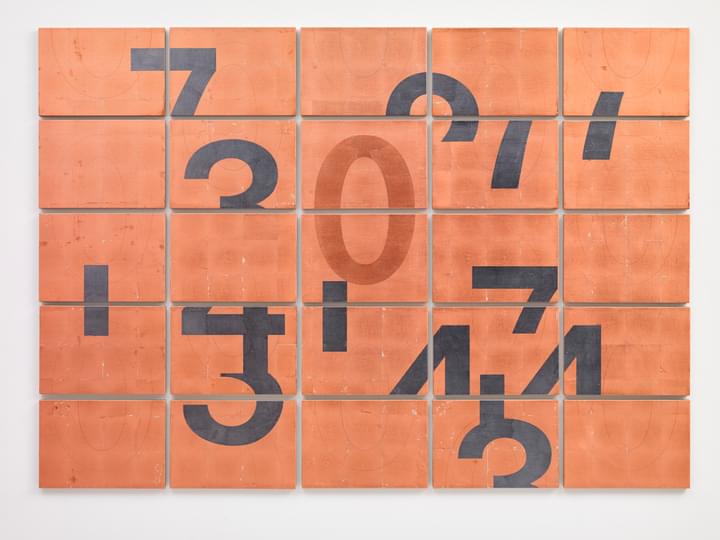

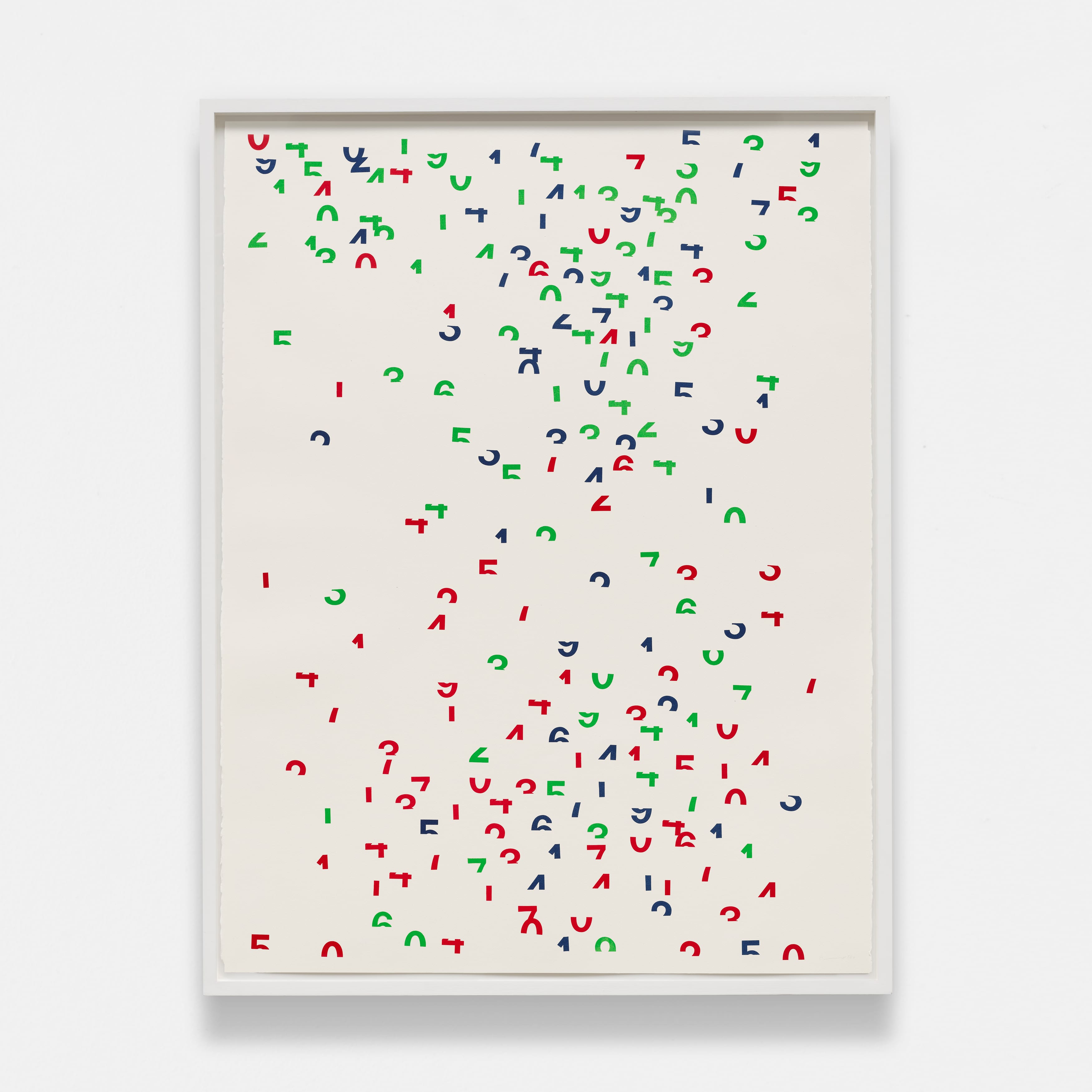

Almond’s paintings similarly invoke the intrinsic logic and communicative potential of numbers. As a primary determinant of human experience, numbers make legible the multidimensional, as Almond affirms: ‘Our cosmic landscape and biological make-up all reside in this language for it informs all extremities, from describing spacetime to underlying genetic code and engineering’. Featuring fragmented integers over a modernist grid, the artist’s paintings are variously executed with concrete-based mineral paint; acrylic gel on mirror; or layers of metal leaf including gold, copper, silver and palladium, to actively respond to both diurnal and artificial light. Visualising numbers as symbols of spiritual invocation, such as the recurrence of zeroes emblematising infinitude, Almond hints at the possibility for numbers to recognise that which resists language and to scale that which surpasses human perspective. The use of numbers attempts to overcome, as Almond describes, the ‘failures in our lexicon to cope with the true scale of things beyond human reach’.

The forms and mechanisms of human industry, including the extraction of raw materials and the development of transportation systems, are a frequent theme of Almond’s films, which vary from single-channel projections to multi-screen installations. These concerns are articulated in films made during the 1990s and 2000s, which focus in particular on train systems and mines. His trilogy of train films begins with Schwebebahn (1995) – a Super 8 film made on Europe’s only suspended urban monorail, in which Almond merges the archaic and futuristic qualities of this engineering into inverted, reversed and slowed footage. Also part of this trilogy are Geisterbahn (1999) and the final work, In the Between (2006) – a complex, multi-screen installation documenting the controversial Qinghai-Tibet railway. The lived reality of manual labour in hostile geographies and isolated locations – such as the Arctic Circle, Siberia, the holy mountains in China and the source of the Nile – is explored in other works, including Schacta (2001), where Almond filmed the activities of a Kazakhstani coal mine, set to a haunting field-recording of a female shaman musician. In Bearing (2007), Almond closely follows a sulphur miner in Indonesia on one of his daily routes, filming with a high-definition camera the worker’s intense journey from the mouth of a crater to the weighing station. During the 2000s, Almond travelled intermittently for a period of ten years to the world’s largest nickel mine in Norilsk, near the Arctic Circle in Russia, documenting this ‘survival on the edge of human existence’ through a moving image work and body of photographs. Several early films focus on similar themes closer to Almond’s heritage, including the intimate work Traction (1999), an ambitious three-screen portrait of his father describing the scars he acquired from years of physical labour. A similar intimacy is evident in If I Had You (2003), another multi-screen film installation that focuses on his grandmother and celebrates her old age with dignity, tenderly depicting her reminiscing about her earlier life.

Starting in the mid-1990s, Almond adopted the form of metal and alloy train plates for a series of text-based sculptures featuring fragments of thoughts, writing or poetry. A reference to the naming tradition of British locomotives, they explore how trains are not just physical interventions in the landscape, but carriers of collective thoughts and emotions. The use of train plates relates directly to Almond’s own biography, being a trainspotter in his youth and travelling extensively by train to broaden his worldview.

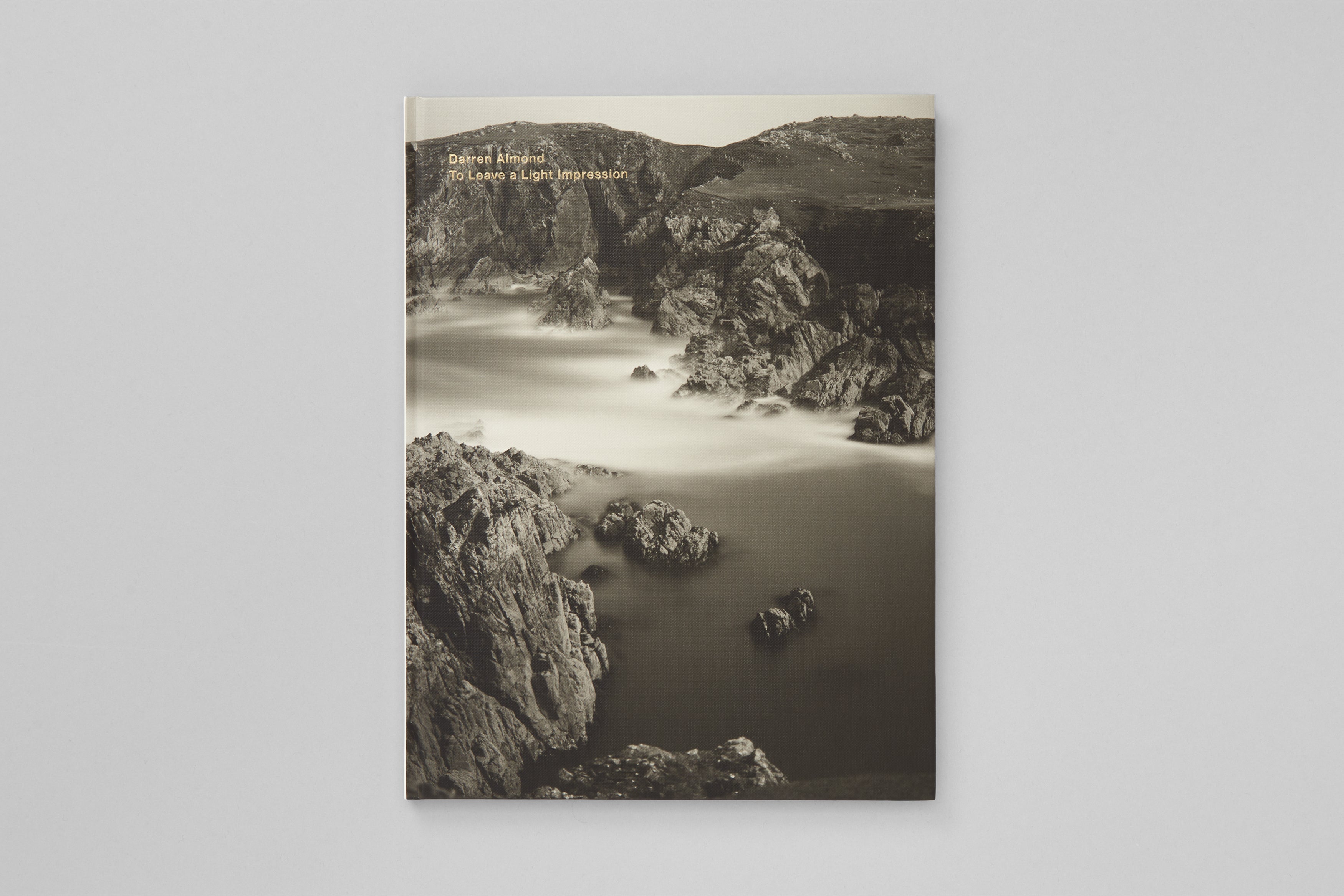

‘I have followed the cycle of the moon for almost two decades and have used it to expose the landscapes of our dreams’, Almond says of his series of ‘Fullmoon’ photographs, produced from 2000 onwards. Taken with variable long exposure times attuned to the shifting atmospheric conditions and using only moonlight as their source, the photographs reference the Romantic legacy and rich history of landscape painting to locate the photograph as an archive of memory. The project began with Fifteen minute moon (2000) in the south of France before Almond looked at locations through the paintings of John Constable, J.M.W. Turner, Caspar David Friedrich, Philip de Koninck and others. Subsequently searching out photographic views in all seven continents, this series has been a constant throughout Almond’s practice. Compressing elapsed time within their image to present ‘a reflective landscape’, these photographs reveal atmospheric details previously imperceptible to the human eye. Shadows are dissipated and wind becomes visible; clouds lose dimension and rivers become stilled; all bathed in unexpectedly brilliant, often haunting light. Seductive, unsettling and devoid of human presence, these otherworldly landscapes chart environmental change and express landscape as a container for memory, with each image surfaced by the celestial object – another charter of time.

Human activity in relation to slow, geological time is the abiding subject of ‘Present Form’ (2012/3), a series of ‘portraits’ of 4,500-year-old totemic, Neolithic and megalithic stones in Stennes, Orkney, and Callanish, Isle of Lewis, Scotland. Connected to measurements of time – possibly forming a lunar clock – the stones’ weathered and moss-covered surface inscribes an archaeology of time, a terrestrial archive. The major work All Things Pass (2012) equally deals with an extension of time, documenting the play of light and the vivid, green algae animating Chand Baori, an intricate 9th-century stone step well in Rajasthan, India. A six-channel video installation, set to unfolding Indian ragas, it foregrounds Almond’s interest in the relationship between maths and nature and its impact on perception and knowledge.

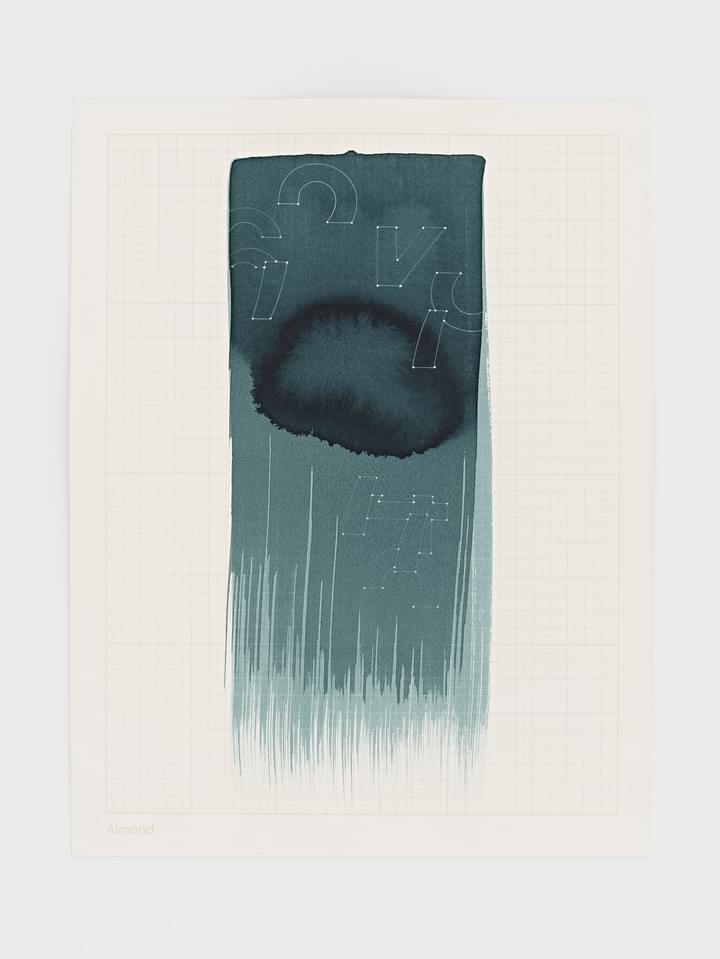

An extension of Almond’s ‘Fullmoon’ works is observed in the artist’s paintings of nocturnal landscapes exhibited in 2016. During a full-moon photographic shoot in Patagonia in 2013, Almond was captivated by the colours and movement in the night sky. Having charted the positions of stars in drawings made over a decade earlier, he turned his attention to the dark sky paradox of space itself. Addressing the colours of the void space, Almond interpreted Heidegger’s notion of the three dimensions of the universe – the past, present and future. In these works, washes of indigo, yellow and temperate red coalesce on the surface of the panels, creating spectra that radiate and absorb the constellations of stars, nebulas, auroras and galaxies that emerge from the surface.

Recent multi-panel paintings, such as Almond’s new series of works, ‘Inari Chimera’ (2023–24), are installed to create a single, extended composition. ‘Inari Chimera’ comprises a matrix of digits in Helvetica font, each symbol and number fragmented as though a cascade of glitching, digitised time. Running horizontally across its centre, six zeroes appear as faint, waning moons, each formed of thin strips of gold. Echoing the titular ‘chimera’ that remains unknowable, these zeroes evoke the integer’s spiritual dimension in that, for Almond, the zero is ‘the nothing that holds everything together’. Across the artist’s large-scale painting, sculpture, photography and moving image, Almond maintains a deliberately ambiguous and enigmatic enquiry into the means by which we think, experience and relate to time.

Darren Almond was born in 1971 in Wigan, UK and lives and works in Norfolk. Solo exhibitions include Museo Cappella Sansevero, Naples, Italy (2025); Jesus College, Cambridge (2019); Villa Pignatelli-Casa della Fotografia, Naples, Italy (2018); Mudam, Luxembourg (2017); Museum Sinclair Haus, Bad Homberg, Germany (2016); New Art Centre, Salisbury, UK (2016); Neue Galerie, Graz, Austria (2015); Bloomberg Space, London (2014); Art Tower Mito, Japan (2013); Sala Alcalá 31, Madrid (2013); Château Gallery, Domaine Régional de Chaumont-sur-Loire, France (2012); The High Line, New York (2011); Villa Merkel, Esslingen am Neckar, Germany (2011); L’Abbaye de la Chaise Dieu, France (2011); Frac Normandie, Rouen, France (2011); FRAC Auvergne, Clermont Ferrand, France (2011); Parasol Unit, London (2008); K21 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf, Germany (2005); Tate Britain, London (2002); Kunsthalle, Zurich (2001); Tate Britain, London (2001); DeAppel, Amsterdam (2001); and The Renaissance Society, Chicago (1999). He has participated in numerous group exhibitions including Fondation Carmignac, Porquerolles, France (2023); Parasol Unit, Venice (2022); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2022); Getty Center, Los Angeles (2021); Fondation Van Gogh, Arles, France (2020); Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2019); Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark (2018); Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna (2017); Centre Pompidou-Metz, France (2016); Royal Academy of Arts, London (2015; 2000); Nottingham Contemporary, UK (2015); Helmhaus, Zurich, Switzerland (2011); 6th Biennale de Curitiba, Brazil (2011); Miami Art Museum (2011); Musée d’Art Contemporain du Val-de-Marne, Vitry-sûr-Seine, France (2010); Tate Triennial, Tate Britain, London (2009); Frac Lorraine, Metz, France (2009); 2nd Moscow Biennale (2007); SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico (2007); The Turner Prize, Tate Britain, London (2005); and 50th Biennale di Venezia (2003).