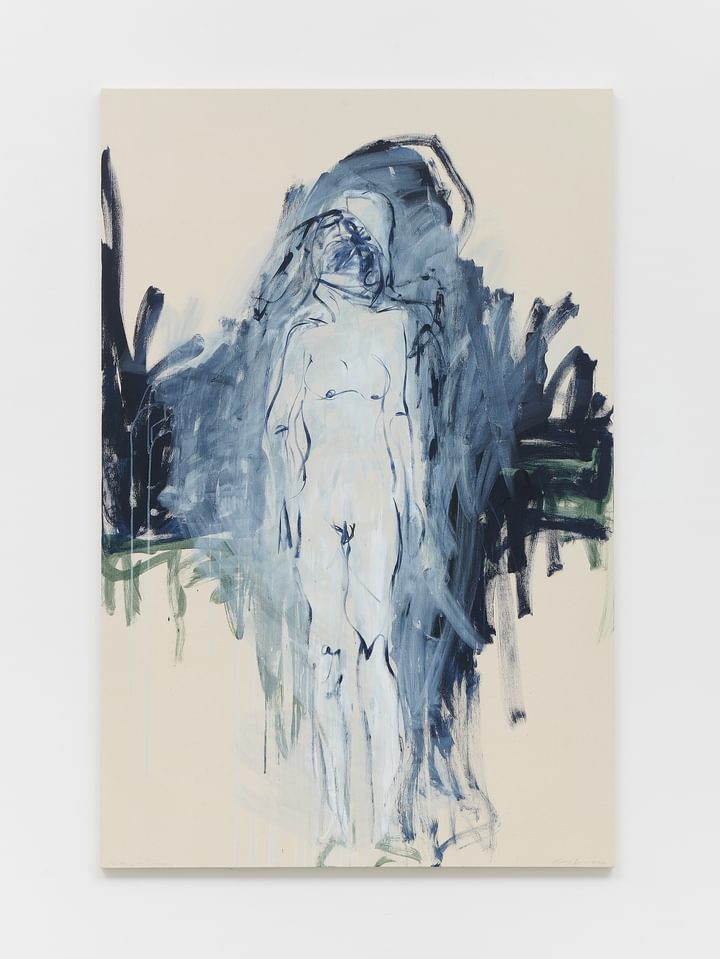

Like A Cloud of Blood, 2022

Tracey Emin

Lives and works in Margate, London and France

B. 1963

Artworks

Exhibitions

Gallery Exhibition

Tracey Emin

I followed you to the end

19 September – 10 November 2024

Gallery Exhibition

Tracey Emin

Lovers Grave

4 November 2023 – 13 January 2024

Gallery Exhibition

Tracey Emin

Living Under the Hunters Moon

25 October 2020 – 13 February 2021

Gallery Exhibition

Tracey Emin

A Fortnight of Tears

6 February – 7 April 2019

Museum Exhibitions

Find out more29 March - 10 August 2025 | New Haven, Connecticut

16 March - 20 July 2025 | Florence, Italy

21 October 2023 - 14 July 2024 | New York

28 May - 2 October 2022

Films

Martin Gayford on Tracey Emin

Writer and art critic, Martin Gayford explores Tracey Emin’s solo exhibition ‘I followed you to the end’ at White Cube Bermondsey in 2024.

Tracey Emin and Martin Gayford

On the occasion of Tracey Emin’s exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey in 2024, the artist was joined in conversation with writer and curator Martin Gayford.

Martin Gayford on Tracey Emin

Writer and art critic, Martin Gayford explores Tracey Emin’s solo exhibition ‘I followed you to the end’ at White Cube Bermondsey.

Tracey Emin at Faurschou

Tracey Emin discusses her exhibition, ‘Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made’ (1996) at Faurschou New York.

Tracey Emin and Courtney Willis Blair

On the occasion of Tracey Emin’s exhibition ‘Lovers Grave’ (2023 – 2024) at White Cube New York, the artist was joined in conversation with Courtney Willis Blair, US Senior Director, White Cube, at The Prince George Ballroom in Manhattan.

Tracey Emin on 'I Cried Because I Love You'

Tracey explores the ideas behind the work in her exhibition 'I Cried Because I Love You' in Hong Kong, 2016.

Emin / Edvard Munch: The Loneliness of the Soul

Edith Devaney, Contemporary Curator at the Royal Academy of Arts introduces the exhibition 'Tracey Emin / Edvard Munch: The Loneliness of the Soul' in 2021.

Tracey Emin on 'How it Feels'

Tracey Emin discusses her film, How it Feels (1996), the title of which she has used for her solo exhibition at MALBA, Buenos Aires.

Tracey Emin on making films

Tracey discusses her approach to film-making with Philip Larratt-Smith.

Harry Weller on Tracey Emin's paintings

Harry Weller, the Creative Director at Tracey Emin's studio discusses her painting methods, describing how she embraces mistakes and constantly reworks the canvas.

Susanna Greeves on Dreamers Awake

Susanna Greeves discusses the work in the exhibition 'Dreamers Awake' at White Cube Bermondsey in 2017.

Tracey Emin on 'I Cried Because I Love You'

Tracey Emin explores the ideas behind the work in her exhibition 'I Cried Because I Love You' in Hong Kong, 2016.

News

Find out more5 November 2024 | White Cube Bermondsey, London

28 October 2024 | London

4 November 2023 - 18 February 2024 | Hanover, Germany

Prints & Multiples

View all Prints & Multiples

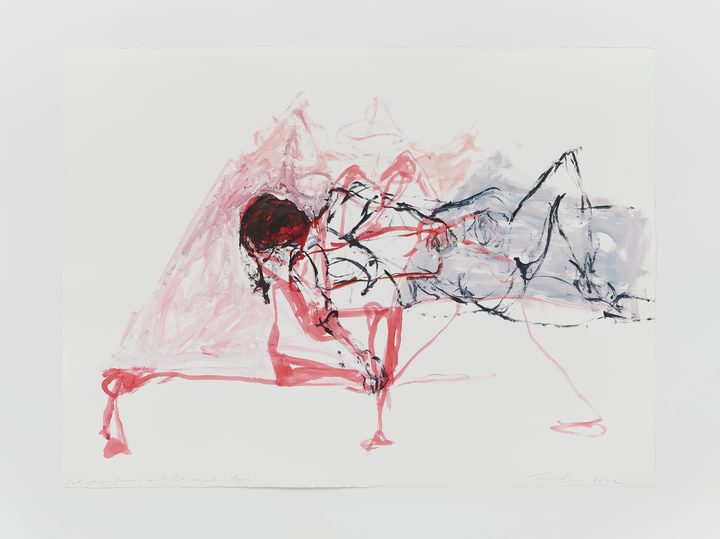

Tracey Emin

The Wedding

2019

Price upon request

Bookshop

Browse the BookshopCreate an Account

To view available artworks and access prices.