Mahama came to prominence for politically charged open-air installations using jute sacks, which are stitched together as a tattered patchwork and draped over architectural structures. In the cities of Accra and Kumasi in Ghana, where he lives and works, he has sited work in locations such as a library, a museum, an airport and a bridge. With Out of Bounds (2015) at the 56th Venice Biennale, he covered the walls of the Arsenale to create a sheathed walkway, a route between the global art context and lives touched by the fabric in the past. Although sourced in the markets of Ghana, the jute sacks are originally fabricated in South East Asia, then imported by the Ghana Cocoa Board to transport cocoa beans, but are eventually used to transport food, charcoal and other commodities at the end of their cycle. Mahama says, ‘I am interested in how crisis and failure are absorbed into this material with a strong reference to global transaction and how capitalist structures work.’ Marked with names, the sackcloth bears the traces of its journey and the people it has encountered, forming a kind of skin for the urban fabric. Textiles hold a central place in Mahama’s practice; he describes them as an archival document, marked with time, form and place. As he explains, ‘the hope is that their residues – stained, broken and abandoned, but bearing light – might lead us into new possibilities and spaces beyond.’

Critical to the artist’s practice is the collaborative process by which he collects, remakes and installs his materials, involving artists, artisans, architects, technicians, traders, scaffolders, bureaucrats and executives, among others. He has photographed the arms of collaborators who have tattooed their names and other biodata on their own skin due to a lack of paper documentation; Mahama’s documentation effects a transformation, from a commodity back to a body. In Non-Orientable Nkansa (2017), hundreds of ‘shoemaker boxes’ are gathered as a single unit, a precarious monument to anonymous labour. Mahama collected the shoemaker boxes either by exchanging new for used ones or by commissioning dozens of people to make them from scraps of wood found in Accra and Kumasi. Similarly, A Grain of Wheat 1918–1945 (2015–18) combines scores of battered ambulance stretchers from the Second World War with replicas, partially re-stretched with household fabrics and smoked fish papers from West Africa, like a painting. Smelling of smoke, engine oil, fish and blood and propped upright in a continuous line, the carriers acquire a metaphorical dimension, for the domino effect of global events on seemingly faraway lives.

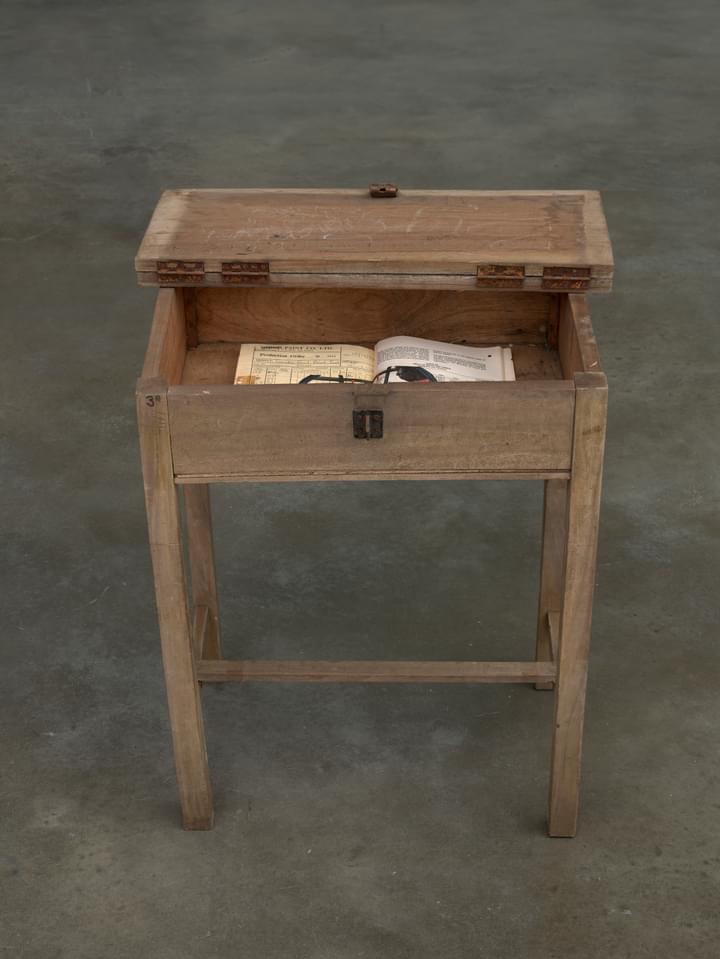

Mahama looks to the period of optimism in Ghana in the 1960s, when West African nations, newly independent from British colonial rule, imagined a way forward, only to break down. The vestiges of Ghana’s train network were being sold for scrap when Mahama rescued them. For Parliament of Ghosts (2019), he had scores of old carriage seats shipped to Manchester. In this way, functional objects become symbols of colonial infrastructure, returned to the source. Afterwards, he had the installation rebuilt as a functional space in Tamale, his birthplace, with the seats enabling visitors to sit together and talk. In Capital Corpses (2019–21), a hundred rusty sewing machines are affixed to colonial-era wooden school desks, which are sectioned and activated by a tier, creating a syncopated cacophony of noise. Once a ubiquitous tool in Ghana, used by labourers to hastily adopt a new trade, the now decommissioned sewing machines were collected by the artist with the intention of ‘resurrecting the ghosts that are in the machines’. They are flanked by blackboards, which, like the jute sacks or the workers’ tattooed forearms, behave as palimpsests; the inscription of notes, names and directions calls attention to the surface as a site of changing meaning. More recently, Garden of Scars (2022) in the church of Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, presented ‘modern tombstones’ to broken relationships: casts and rubbings of the gravestones on the floor of the church and of the floors and walls of Dutch forts on the Ghanaian coast are mixed with materials in Ghana that would have historically been exported from Europe and cast with soil and cement.

Mahama’s active approach to the circular economy is driving his commitment to the development of contemporary art in Ghana – now a flourishing aspect of his artistic practice. By bringing sacks and railway parts into the art economy, Mahama has transformed these materials into a commodity more valuable than the products they were once used to transport. In recent years, he has channelled the proceeds into establishing interdisciplinary institutions close to Tamale. Now obsolete, the enormous concrete silos built to store grain and other food are a potent symbol, one that Mahama is mobilising in a project of tangible regeneration. During excavation of Nkrumah Volini (whose name, attributed by locals, roughly translates as ‘the void’), he discovered that in its disuse it had become a haven for wildlife, including a colony of bats, who continue to inhabit the building now it is a cultural centre. In April 2021, he turned Nkrumah Volini into a new cultural centre, joining Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA), which has mounted exhibitions with the international loan of historical materials since its opening in 2019, and Red Clay, in nearby Janna Kpeŋŋ, which opened in 2020 and encompasses artist studios, recording facilities and repurposed airplanes. Through the consortium, Mahama is deploying art practice to fuse social and cultural transformation in the local area.

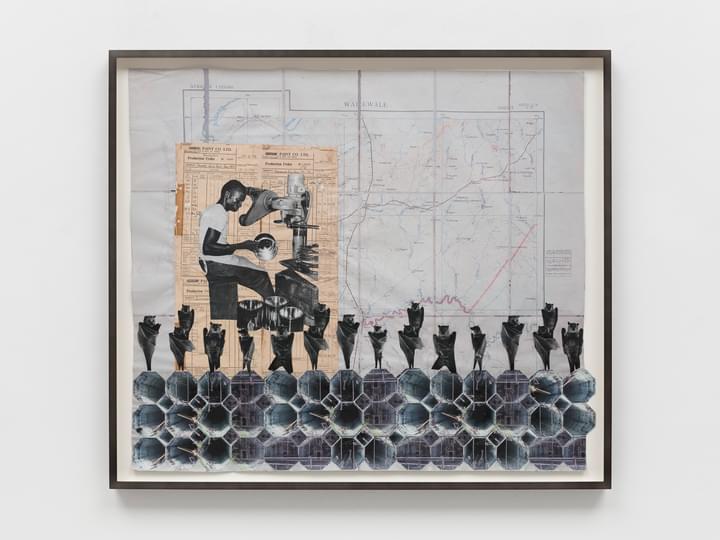

The bats of Nkrumah Volini – a symbol of death and rebirth – were the inspiration for Lazarus (2021), a grouping of suspended forms constructed from armatures of metal rebar. Draped with tarpaulin (originally used for covering cargo) and dark with oil, it has a spectral quality that speaks to Mahama’s wider practice of exhumation. On a smaller scale, Mahama’s collages combine images of silos and bats with archival notes, drawing and photographs, colonial era maps, bank notebooks, orders and ledgers from the 1960s and 70s. The collage techniques of blotting, spoiling and appropriation relate to historical colonial domination and the punishing conditions of the climate crisis.

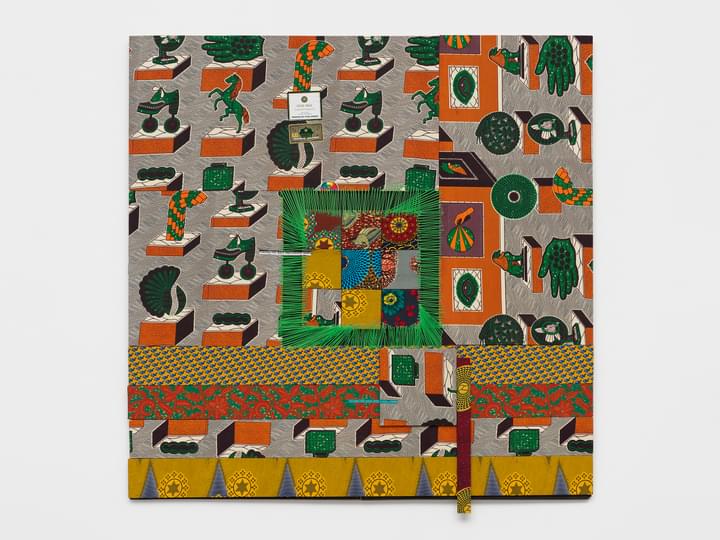

Mahama’s training in painting at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi surfaces in what he calls ‘fabric paintings’. Pieced together from swatches of fabric the artist has collected over years, these employ Dutch wax cloth, an imitation batik that is synonymous with African design but mass-produced in Europe and China. With brightly coloured stitching visible between sections, these dazzling compositions juxtapose remnants of mass-produced fabric within unique works that comment on the commodification of identity. The geometric construction, with vertical and horizontal sections that interlock and overlap, invites the eye to search through a dissonant array of patterns. By using titles from Fela Kuti, the Pan-African musician and political activist, from the seminal writer Chinua Achebe and from leading Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, he embeds these works within cultural constructions of reality. In places the fabric exceeds the limits of the canvas frame; as the artist says, ‘This is an African story, with ideas of freedom beyond the chaos.’

Ibrahim Mahama was born in 1987 in Tamale, Ghana. He lives and works in Accra, Kumasi and Tamale. Solo exhibitions include Kunsthalle Osnabrück, Germany (2023); Oude Kerk, Amsterdam (2022); Frac Pays de la Loire (2022); The High Line, New York (2021); University of Michigan Museum of Art (2020); The Whitworth, University of Manchester (2019); Norval Foundation, Cape Town (2019); Tel Aviv Art Museum, Israel (2016); and K.N.U.S.T Museum, Kumasi, Ghana (2013). He has participated in numerous group exhibitions including Sharjah Biennial 15 (2023); 18th International Venice Architecture Biennale (2023); the 35th Bienal de São Paulo (2023); Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2021); Centre Pompidou, Paris (2020); 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020); Stellenbosch Triennale (2020); 6th Lubumbashi Biennale, Democratic Republic of the Congo (2019); Ghana Pavilion, 58th Venice Biennale (2019); Documenta 14, Athens and Kassel (2017); Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University (2016); Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen and Holbæk (2016); 56th Venice Biennale (2015); and Artist’s Rooms, K21, Düsseldorf (2015). Mahama was also appointed Artistic Director of the 35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana (2023).