I Beam, 1961

Al Held

Born in Brooklyn, New York

(1928 – 2005)

Artworks

Exhibitions

Gallery Exhibition

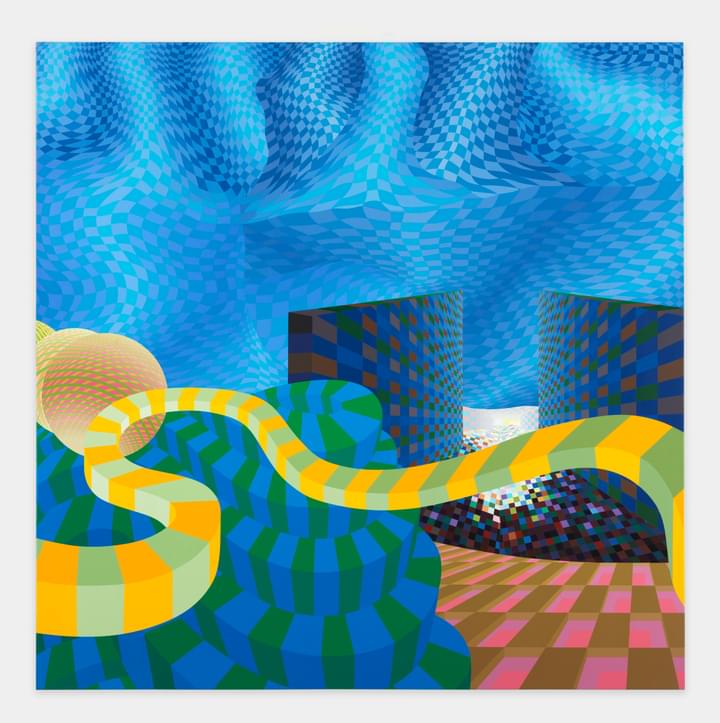

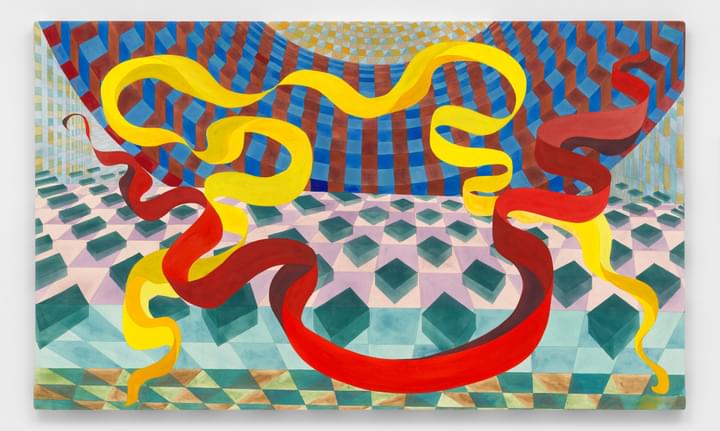

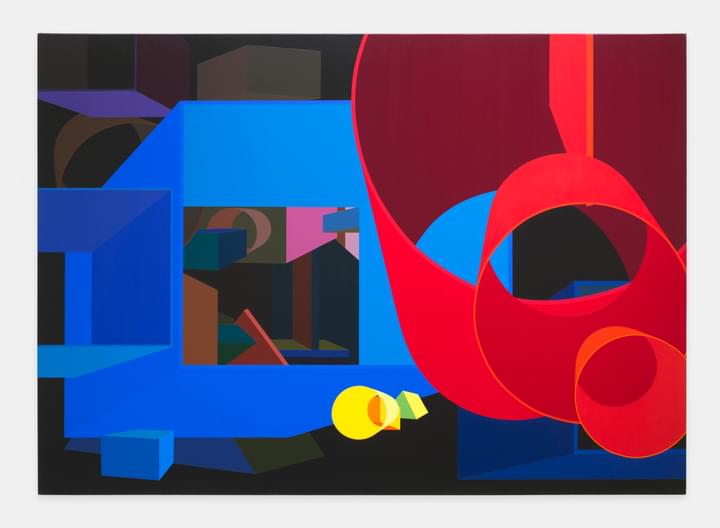

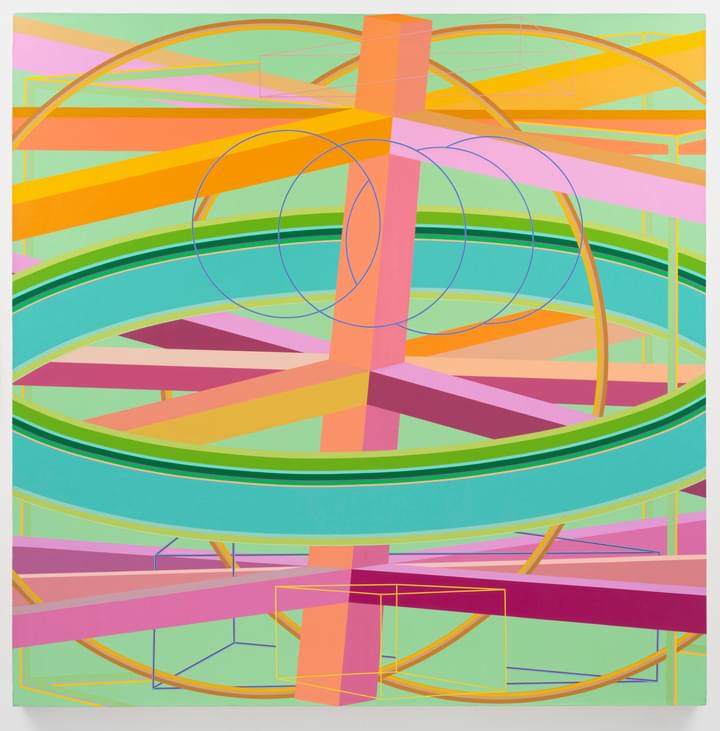

Al Held

About Space

27 June – 1 September 2024

Gallery Exhibition

Al Held

Watercolours

19 April – 27 May 2023

Gallery Exhibition

Al Held

28 January – 28 February 2021

West Palm Beach

Gallery Exhibition

Al Held

The Sixties

20 November 2020 – 27 February 2021

Museum Exhibitions

Find out more19 October - 8 December 2019

21 November 2018 - 22 April 2019

Films

Daniel Belasco on Al Held

Daniel Belasco, Executive Director of the Al Held Foundation, explores the artist’s monumental exhibition ‘Al Held: About Space’ at White Cube Bermondsey.

Daniel Belasco on Al Held

Daniel Belasco, Executive Director of the Al Held Foundation, explores the artist’s monumental exhibition ‘Al Held: About Space’ at White Cube Bermondsey.

Marcia Tucker and Al Held at Whitney Museum of American Art

Al Held in conversation with Marcia Tucker ahead of his 1974 retrospective ‘Al Held’ Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

John Good on the life and career of Al Held

John Good gives an overview of the work of Al Held, tracing his career from his first 'pigment' paintings to later hard-edged canvases.

Michael Craig-Martin and John Good on Al Held

Michael Craig-Martin and John Good discuss the life and work of Al Held. Artist Michael Craig-Martin attended Yale and studied with Al Held.

News

Find out more22 September 2019

Create an Account

To view available artworks and access prices.