Born in Germany in 1945 at the close of World War II, the realities of destruction and rebirth form the foundation of his practice. Despite living and working in France since 1992, he has said that ‘my biography is the biography of Germany’. Initially working from this personal framework, exploring subjects and symbols to consider the fraught territory of Germany’s national identity, Kiefer’s practice has since expanded to include literature, music, religion, mythology, alchemy, astronomy and mysticism. In these diverse fields, Kiefer discerns affinities in the work of Richard Wagner, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Celan, James Joyce and Ingeborg Bachmann, each informing several cycles of works. Likewise, more esoteric figures including Russian experimentalist Velimir Khlebnikov or English alchemist Robert Fludd have provided inspiration. This symphonic abundance of knowledge and language animates Kiefer’s own reading and understanding of the turbulency of human history.

Kiefer has remarked that his work forms ‘an unbroken continuum’ in which ‘chronology is dissolved’. He elaborates, ‘I alone am its evolution in both directions: forwards and backwards’. In this temporal oscillation, Kiefer leads the viewer into new worlds formed of labyrinthine association and symbolism. Characteristic of his pursuit is a sense of desolation, ruination and the resiliency and ambiguity of signs, allowing images, objects and symbols to intertangle and invigorate new meaning. Kiefer’s infinite expansion of space and time has been negotiated through divine, heroic or tragic figures, legendary iconographies, supernatural genealogies, cosmologies, scientific theories and classical, Germanic and Nordic mythologies. These are subjects at the horizons or limits of human thought, yet each relates intimately to conceptions of the human condition.

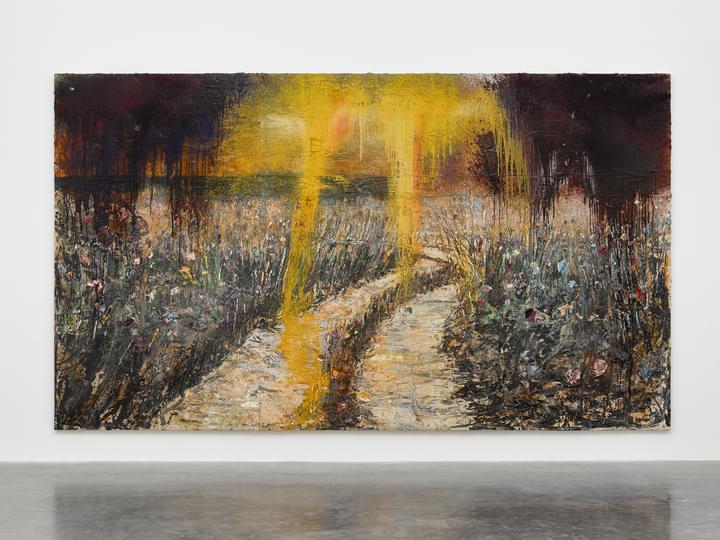

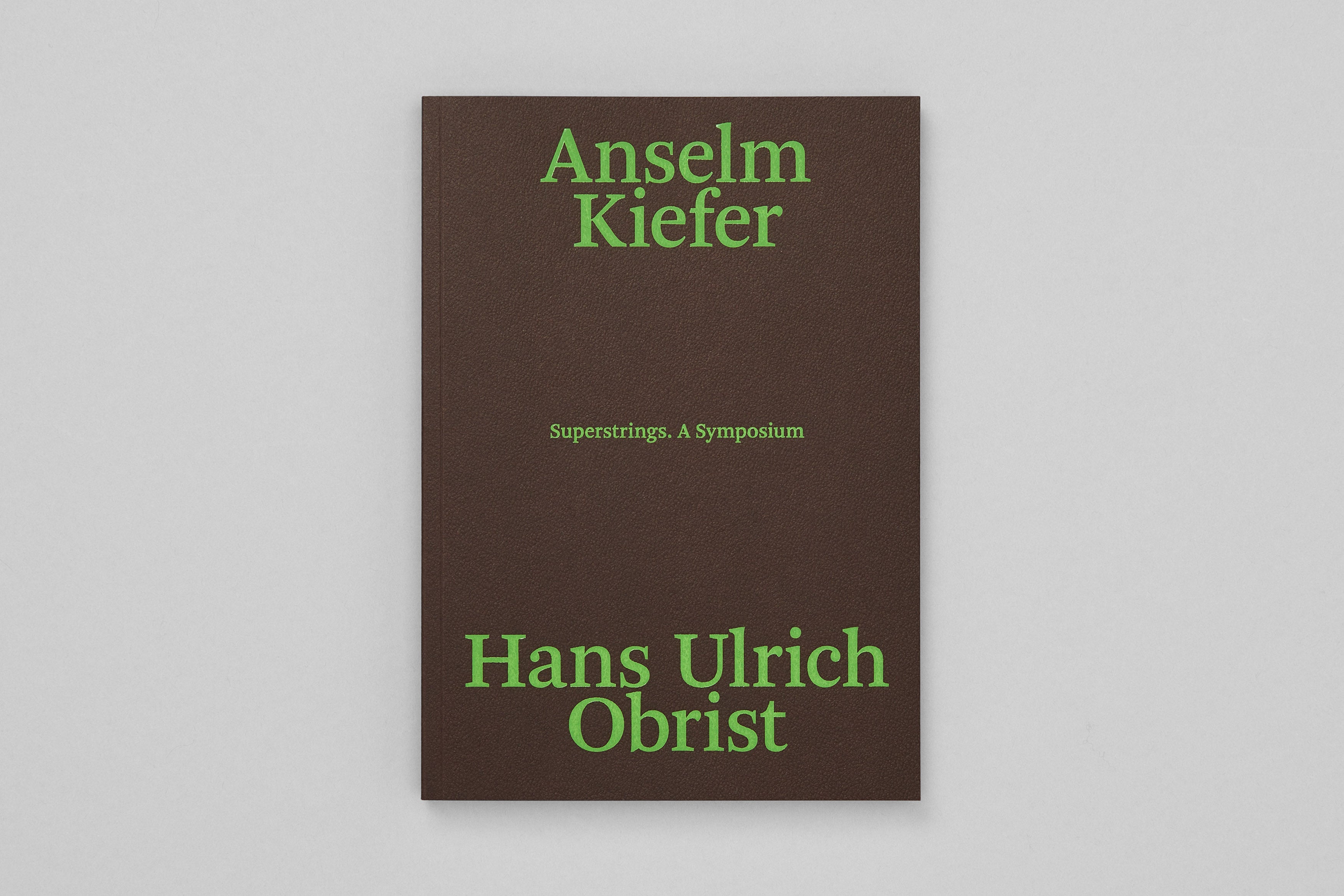

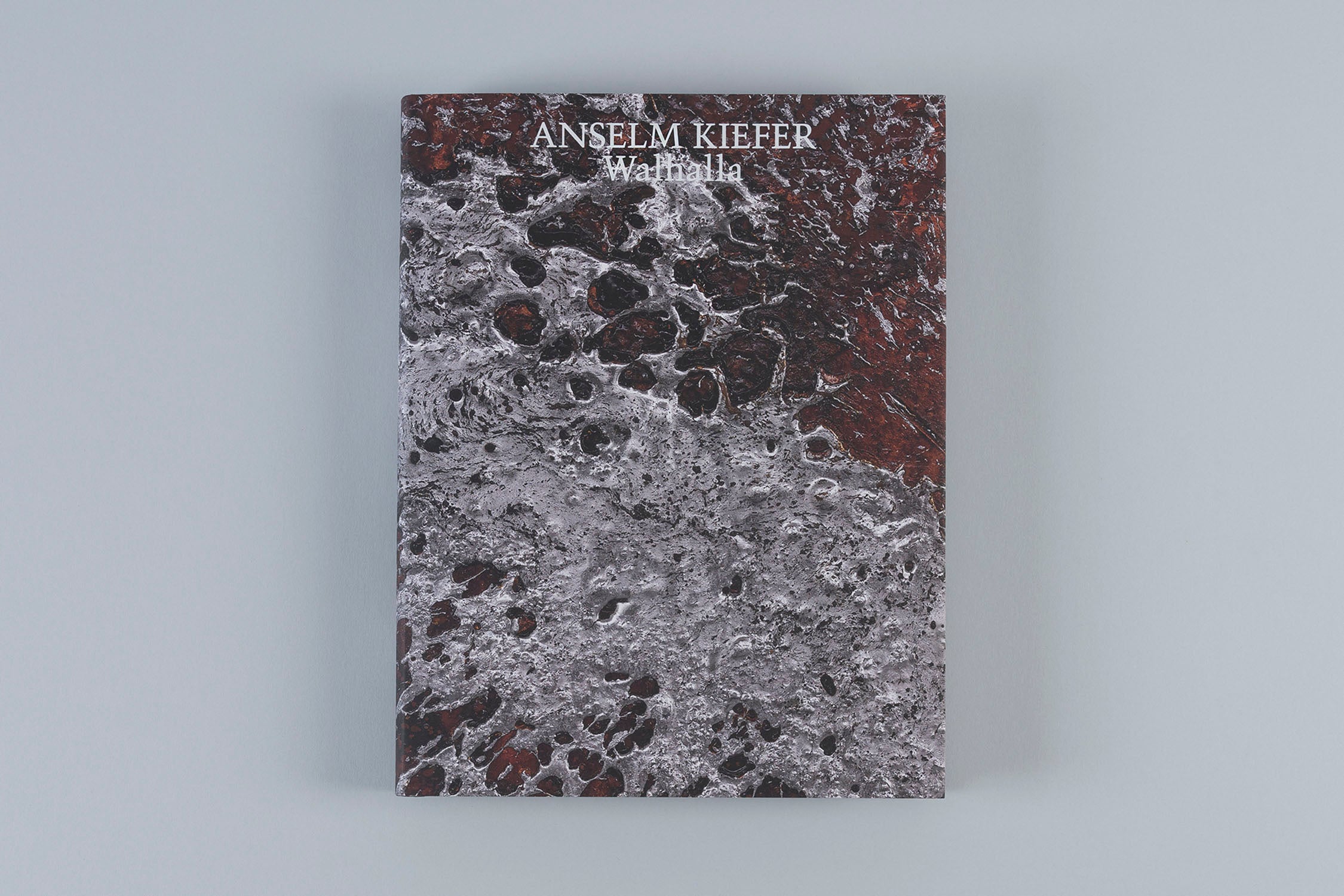

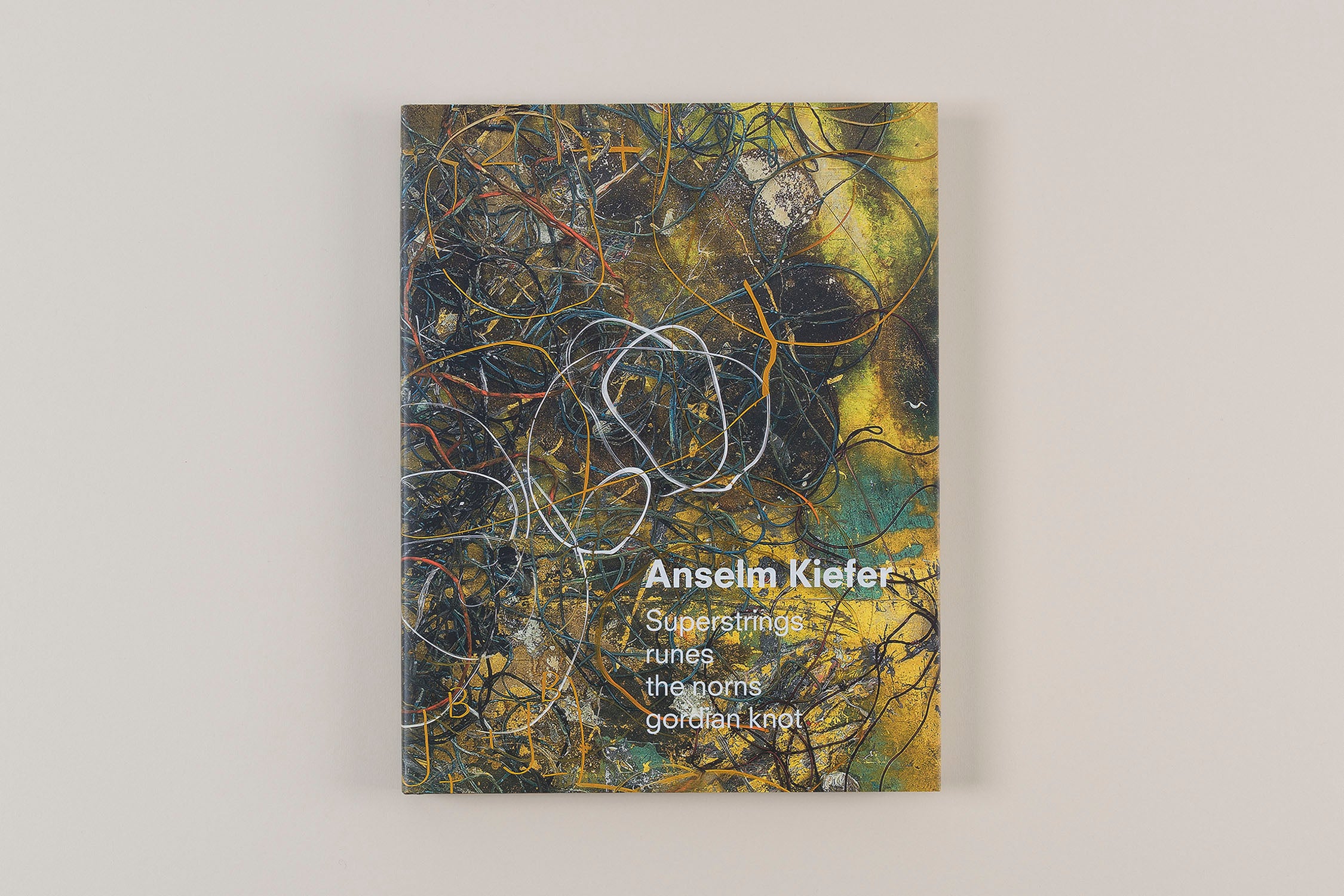

In his monumental paintings, the enigmatic symbolism of barren earth is repeatedly employed to presage entropy and destruction, while other forms of mnemonic iconography, such as vast, classical architectural structures, receding railway tracks, furrowed fields or star-filled skies invoke endless cycles of human endeavour. Regenerating and expanding certain seminal motifs, Kiefer ambitiously connects diverse histories and bodies of knowledge: Norse mythology with nature and National Socialism in ‘Walhalla’ (2016-17); string theory with linguistics and ancient mythology in ‘Superstrings, Runes, The Norns, Gordian Knot’ (2019–20); and James Joyce’s writings in ‘Anselm Kiefer – Finnegans Wake’ (2023). Across these epic exhibitions, Kiefer’s work reawakens ancient histories and offers new readings of established narratives.

The expansive and permeant subject matter of Kiefer’s work is realised in similarly diversified material. Concrete, copper, glass, shellac and lead provoke states of collapse, dereliction and decay, while soil, sand and straw conjure a mutability of life and emergent vitality. Transitional forms and perishable matter embody what Kiefer calls ‘the effervescence of change’. Harnessing the inherent spiritual energy of these materials, the artist destabilises the boundary between art and nature, history and myth, illusion and reality.

Recognising the primary cognitive mode of history as that of narrative and storytelling, language is also assumed as material in Kiefer’s work. Poetry becomes a form of navigation, as Kiefer says, ‘they are like buoys in the sea. I swim to them, from one to the next […] without them, I am lost.’ The circuitous structure, density of language and accrual of meaning of Joyce’s writings, for instance, embeds language from a multitude of cultures and weaves them into a singular, protean voice. This cohesive entanglement is emblematic of Kiefer’s practice and his interest in language, seen foremost in his creation of books as both containers of thought and reservoirs of imagery. As objects which transmit knowledge, these sculptural books encapsulate, as Kiefer says, a means ‘to find my way through the old stories.’ Created to be read in a sequential manner, they feature assorted media, from watercolour to collage, photography to print, as well as sand, straw, metal, detritus and other unusual elements. As an open-ended textual system, these books hint at a diaristic presence while also evoking the continuity of culture more broadly. From the late 1970s onwards, lead became a significant material in these books as well as in his paintings, sculptures and installations. As with many of Kiefer’s materials, lead is loaded with signifiers – the substance is heavy and inert yet also malleable and full of alchemical potential, embodying, as Kiefer says, a ‘material that seemed to reach beyond the insuperable limits of ordinary reality’.

Kiefer’s books echo the complex inventories that have often constituted his seemingly entombing installations. Looming over the viewer as towers of taxonomy, the catalogued items which feature in Kiefer’s inventories – sunflowers, DNA helixes, boulders, trolleys, straw – appear desiccated, barren and ostensibly abandoned. Much like the artist’s interest in the edges of comprehension and the compacted presence of his books, the purpose of this deconstructive system remains opaque to the viewer. Yet the imaginative realm of Kiefer’s material library preserves memory in a fictionalised space of history, hinting at the political, ideological and emotive drives at work in the making of an archive itself.

Kiefer's immersive studio environments are an essential component of this methodology, functioning as both laboratories and reserves that allow for research, accumulation and material transformation. Often depicted in his paintings, his studios include his current location: a former department store warehouse in Croissy, on the edge of Paris; a schoolhouse and old brick factory in Buchen, south-west Germany; and a site of almost 100 acres in Barjac, near Avignon in southern France, where he was based for many years after he first moved to France. This last site (open to the public since summer 2022) was gradually developed into what is now known as La Ribaute: a gesamtkunstwerk that comprises 52 buildings, an amphitheatre and more than 70 major works in situ, connected by above-ground paths and underground passages.

The multiple evolutions and continued expansiveness of the artist’s practice extends to revisions and reflections on previous work. Undermining the artwork as a consummate, hermetic creation, Kiefer often discards canvases for several years – burying them, marking their surfaces with acid, earth or water, or leaving them to weather in the rain. The artworks enter new permutations and become reinvested and reinscribed with energy, subject to a sequence of corruptive actions and distressed alteration. In this way, the painting is treated as an object with an almost sculptural presence, bearing signs of a wounded corpus, at once injured, healing and deteriorating. This treatment aligns with Kiefer’s practice at large, which considers the process of creation as both a mining of the self and a mining of the past, encouraging latent patterns and correspondences to surface.

Across work that spans enormous timescales, saturated with sources from the past, Kiefer draws emotional, romantic and mournful force from conflicted depths, creating work that ultimately affirms a subjective measure of time. As Kiefer attests: ‘I am then in the matter, in the paint, in the sand, directly in the clay, in the darkness of the moment. Because the spirit is already contained in the material. [...] It is a strange, contemplative internal state, but also a form of suffering in its lack of clarity.’

Anselm Kiefer was born in Donaueschingen, Germany in 1945 and has lived and worked in France since 1993. He has exhibited widely, including solo shows at the Royal Academy London (2025); Stedelijk Museum and Van Gogh Museum (2025); Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (2025); Nijo Castle, Kyoto (2025); Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, Italy (2024); LaM, Lille, France (2023–24); Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Netherlands (2023–24); Palazzo Ducale, Venice, Italy (2022); Grand Palais Éphémère, Paris (2021); Franz Marc Museum, Kochel, Germany (2020); Couvent de La Tourette, Lyon, France (2019); Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo (2019); The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia (2017); Albertina Museum, Vienna (2016); Centre Pompidou, Paris (2015); Royal Academy of Arts, London (2014); Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel (2011); Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (2011); Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark (2010); Grand Palais, Paris (2007); Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain (2007); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California (2006); Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas (2005); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1998); Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin (1991); and The Museum of Modern Art, New York (1987).

In 2023, Kiefer was awarded the Antonio Feltrinelli International Prize for the Arts, as well as being awarded the prestigious Prize for Understanding and Tolerance in 2019 by the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and in 2017 he was awarded the J. Paul Getty Medal. In 2007 Kiefer became the first artist since Georges Braque 50 years earlier to be commissioned to install a permanent work at the Louvre, Paris. In 2009 he created an opera, Am Anfang, to mark the 20th anniversary of the Opéra National de Paris. In November 2020, Kiefer unveiled a new series of work for the Panthéon in Paris, including a permanent installation comprised of six vitrines. Together with a composition by the French contemporary composer Pascal Dusapin, it forms an ensemble of new works commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron. This marks the first time since 1924 that such a commission has been effectuated for the Panthéon.