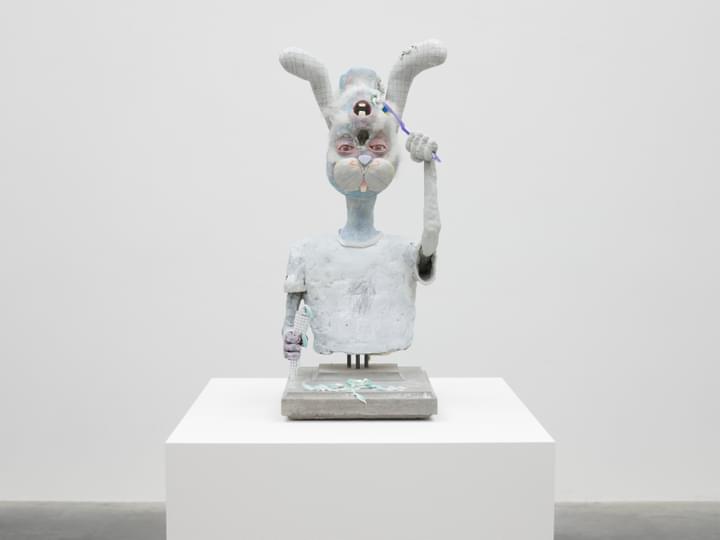

Hare, 2022

David Altmejd

Lives and works in Los Angeles

B. 1974

Artworks

Contact us about available David Altmejd works

Exhibitions

Gallery Exhibition

David Altmejd

The Serpent

14 March – 19 April 2025

Gallery Exhibition

David Altmejd

23 November 2022 – 21 January 2023

Online Exhibition

David Altmejd

Body of Origin

27 July – 3 September 2020

Online

Gallery Exhibition

David Altmejd

The Vibrating Man

26 March – 18 May 2019

Films

David Altmejd at White Cube New York

David Altmejd tours his exhibition ‘The Serpent’ at White Cube New York, which marks the latest evolution in his practice.

David Altmejd at White Cube New York

David Altmejd tours his exhibition ‘The Serpent’ at White Cube New York, which marks the latest evolution in his practice.

David Altmejd

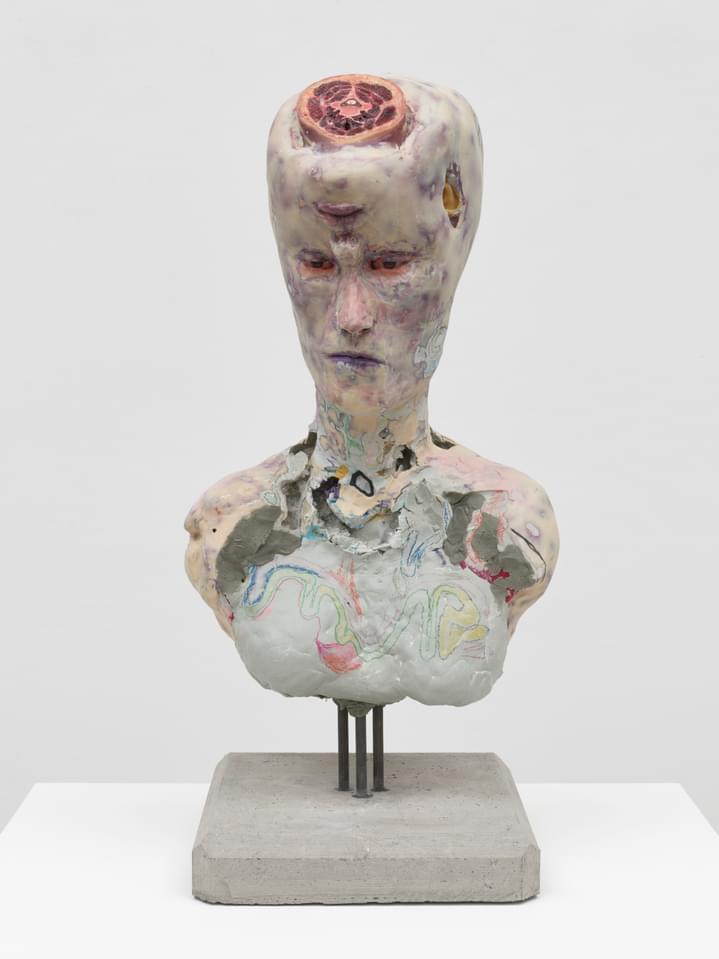

On the occasion of David Altmejd’s exhibition at White Cube Mason’s Yard (2022 – 2023), the artist shares his strategies for generating energy within his sculptures, bestowing them with their own intelligence and multifaceted personality.

Prints & Multiples

View all Prints & MultiplesMuseum Exhibitions

View all news7 November 2025 – 24 January 2026 | Montreal, Canada

Create an Account

To view available artworks and access prices.