Avid consumers of their surroundings, nearly all their subject matter is sourced within walking distance of their home and studio in Fournier Street, East London, where Gilbert & George have lived and created art together for nearly sixty years. Nearby, The Gilbert & George Centre, which opened in April 2023, provides a permanent home for their art and archive. Alert to the turmoil of the city through its ceaseless churn of material, they are ‘visionary artists in the lineage of William Blake’, says critic Michael Bracewell. Their pictures have been populated by skinheads, chewing gum, turds, semen, hoodies, hipsters and nitrous oxide canisters. ‘We’ve always been fascinated by the detritus of life,’ they say, ‘what is left over, what is in the gutter, what is not of interest to anyone.’

Gilbert and George met in 1967, on the advanced sculpture course at St Martins School of Art, where they dissolved their individual identities, and have existed and exhibited as Gilbert & George ever since. They made their first ‘living sculpture’ as students, to great acclaim: in Singing Sculpture, the artists sing along to a recording of Flanagan and Allen’s old-time music-hall hit ‘Underneath the Arches’, all the while moving mechanically, their faces covered with metallic paint like street entertainers as human statues. Always happy to elaborate, they have said, ‘We think of ourselves as two funny tramps, rather than artists according to the popular idea.’ An anthem to down-and-outs, the song became a mantra for the artists, who, cast out from their individual personalities, were also – they claimed – sidestepping the art establishment. The balladeers were invited to stage Singing Sculpture in galleries and institutions all over the world, with renditions lasting from minutes to hours.

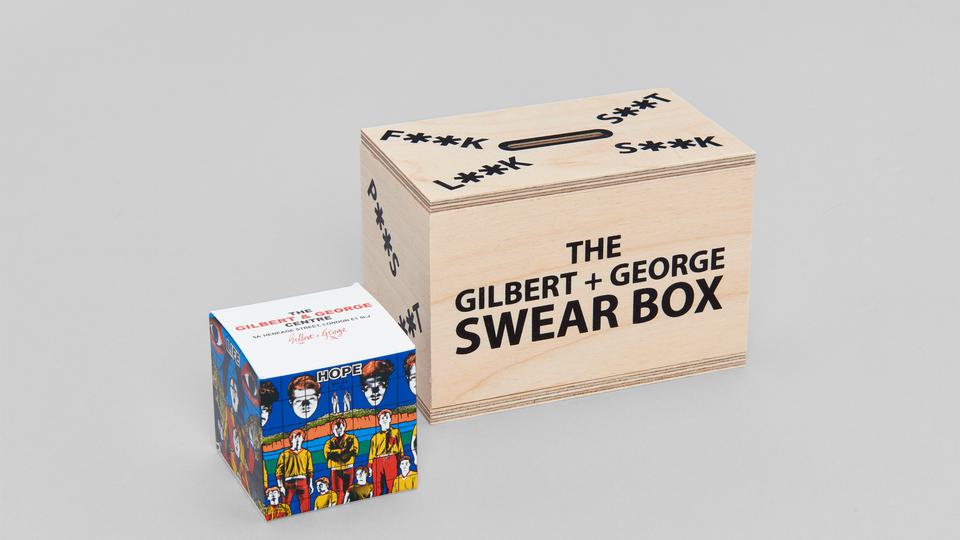

In the 1970s their practice encompassed an expansive idea of sculpture: ‘postal sculptures’, ‘charcoal on paper sculptures’, ‘lecture sculptures’, ‘book sculptures’. The sculpting of their unified image is already at play in George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit (1969), a double self-portrait formed of two photographs, conjoined down the centre fold, a ‘magazine sculpture’ that was published as well as exhibited. The artists smirk into the camera, with paper letters pinned across their jackets and ties spelling out swear words. ‘Always be smartly dressed, well groomed, relaxed, friendly, polite and in complete control’, as they decreed in an accompanying text, ‘laws of sculptors’, in 1969 – a rule they abide by to this day. In Dark Shadow No.6 (1974), the artists seem to blend in profile, while superimposed details of the wood panelling at Fournier Street interweave like suit fabric under the microscope.

Invariably the artists feature in their output as both subject and object, artwork and artist; they are the protagonists of the complex pictorial drama they have created. They have depicted themselves naked, recasting the male nude as a defenceless figure, rather than one of strength. They have exposed themselves in vulnerable states: most notably in the Drinking Pieces (1972–73), when they embarked on a period of destructive behaviour just as they were achieving professional approval. Their loose state is mimicked in art comprised of images that are in and out of focus, distorted or over-exposed, with frames tumbling at angles or strewn over the wall. In the two versions of The Glass (1973), pictures of the artists drinking and of numerous receptacles are used to form the outlines of two martini glasses, so that we are seeing double.

Gilbert & George’s appropriation of mass media, of commercially manufactured images and texts, including postcards, telephone box cards, flyers, street signage and tabloid headlines, relates to their famous motto: ‘Art for All’. They began making ‘postcard sculptures’ in 1972, shortly after they gained recognition in the art world, trawling antique shops for old postcards, which they assembled horizontally and vertically in tight compositions with an overall outline. ‘You can find all your feelings in postcards’, they say, and the cheap souvenirs offer a shortcut to the sentimental, picturesque or nostalgic in arrangements that serve as ‘mindscapes’. In 2009 Gilbert & George returned to the medium after a twenty-year hiatus with the ‘Urethra Postcard Pictures’, whose 564 works comprise the single largest group of works the artists have made. Their innovation was to arrange thirteen cards in rectangles, each punctuated by one card in its central space, an ‘angulated’ translation of the symbol for a urethra used by Victorian theosophist CW Leadbeater. These dazzling bursts of ephemera, viewed collectively, propose a view of imagery as excretion: no one subject dominates, there is an equivalence between images of national identity (Union Jacks, beefeaters, battleships, pugs) and of a sexual society (cards promoting sexual health or advertising sex work).

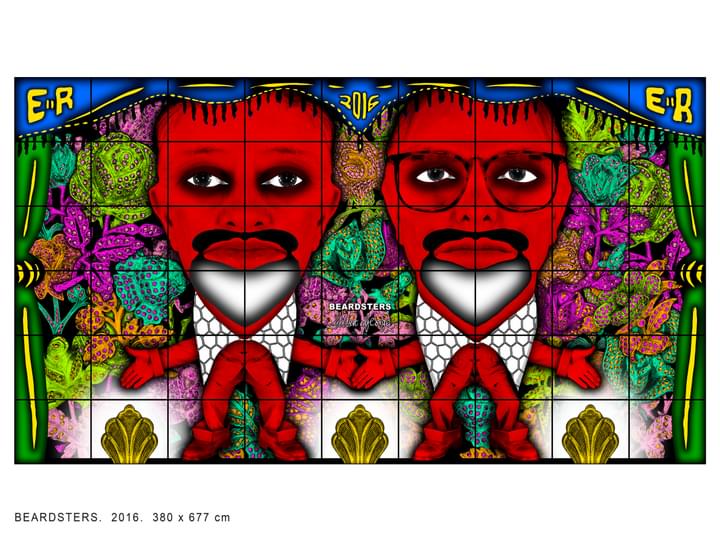

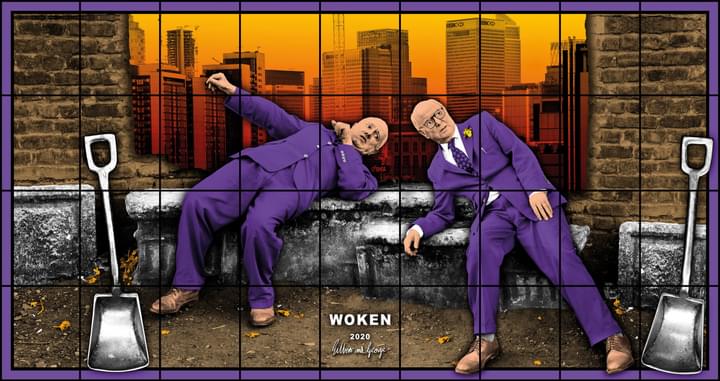

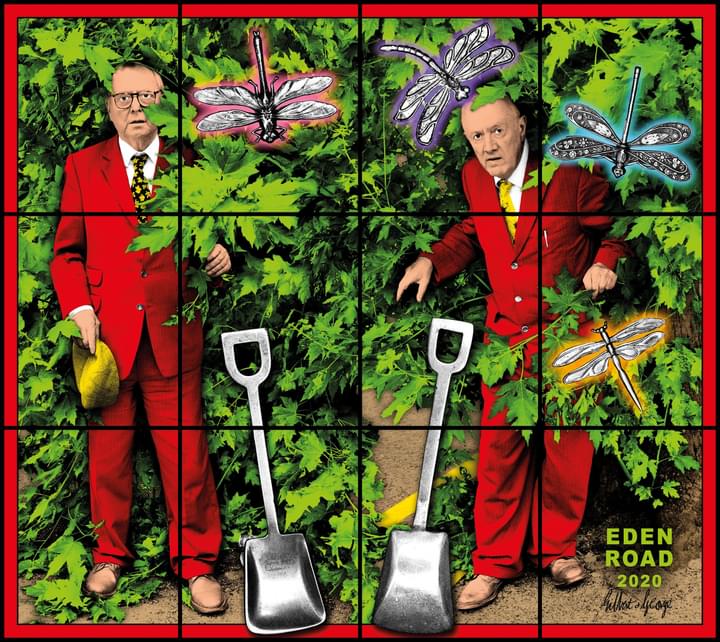

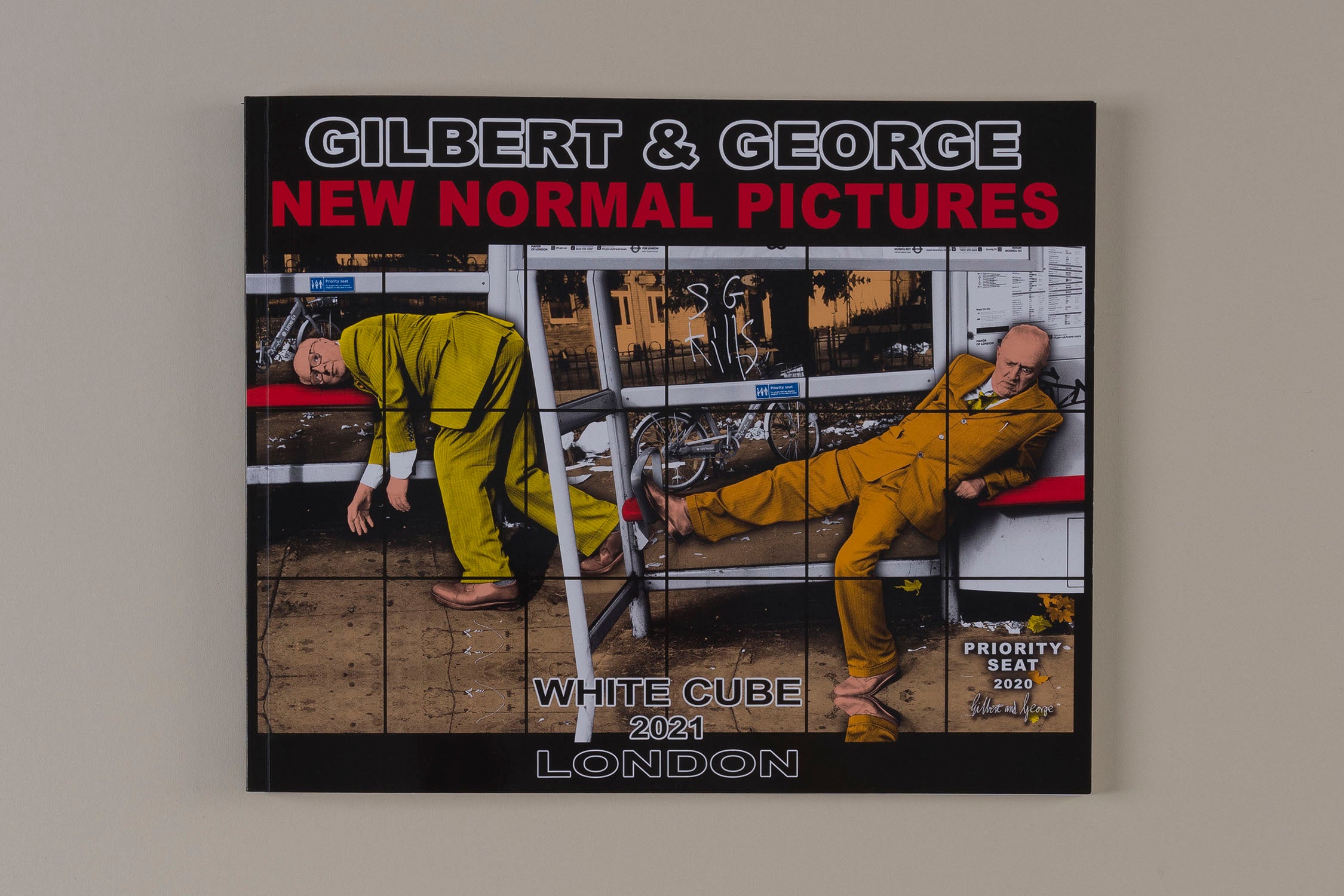

As demonstrated by Gilbert & George’s epic 2007 retrospective at Tate Modern, London – the biggest survey of any artist to be held there – accretion is a significant tool in their arsenal. Gilbert & George immerse the viewer in a universe entirely of their own making, their proclivity for the seamier aspects of urban life channelled through a formal visual language of symmetry and discipline. They started making their signature multi-part pictures by using images as framed components, each part contributing to the bigger picture. At first, they arranged black-and white images across the wall to create an overall shape, as in the cloud-like ‘Nature Pieces’ of 1971; subsequent pictures form a specific shape, dictated by the content, such as the artists’ trademark initials, G and G (1973). Mounted within severe black frames, the prominence of the borders emphasises the fragmentation of the subject matter. The space between the images was reduced, until finally the photo pieces developed into single panel works divided in a grid – a device that draws attention to the picture plane. The grid enabled Gilbert & George to create large-scale compositions, unifying multiple shots in one place, and expanding in units like the construction of high rises. They responded to political and social crisis by moving through dark themes – depression, alcohol, madness, racism and despair – with the grid at times implying the social structures that bind, at others, the barriers that divide.

While the grainy quality of the early black-and-white pictures leant them a certain roughness, by the 1980s, the pictures were saturated with colours, echoing the intensity of billboard advertising but also, in the ‘NEW TESTAMENTAL PICTURES (1997) or ‘SONOFAGOD PICTURES’ (2005), making an allusion to stained glass windows that strikes a discordant note in their confrontation of religion. Gilbert & George have harnessed digital technology to create a proliferation of densely layered images, starting with the ‘GINKGO PICTURES’, made for their representation of Great Britain at the 2005 Venice Biennale, which deploy fantastical arrangements of leaves from Ginkgo biloba trees – a symbol of longevity that grow in the artists’ neighbourhood. Magpies for meaning, in the kaleidoscopic ‘JACK FREAK PICTURES’, (2008), the artists’ bodies, at times fragmented or contorted, are incorporated as emblems on a par with the Union Jack, medals, flags, maps and graffiti.

Most recently, the ‘CORPSING PICTURES’ (2022) show the artists detaching from reality. The title could refer to dead bodies, or to theatrical slang for an actor who slips out of character during a performance, by either forgetting their lines or cracking up. In CRAVATS (2022), for example, the artists appear with their eyes closed, as if sleeping, with customarily stiff white collars and ties constructed from bones on a background of decaying plant matter. For Gilbert & George, to the last, the fourth wall remains inviolable, since there is no division between art and life. The mood, Bracewell writes, may be ‘dream-like, crazily vaudevillian or withdrawn; likewise it can be anxious, violent and confrontational. Most usually, it is a mix of all these states – replicating the ways in which we experience and respond to the unpredictable pageant of modern life.’

Gilbert was born in the Dolomites, Italy in 1943 and George was born in Devon, UK in 1942. Gilbert & George live and work in London. Solo exhibitions include Hayward Gallery, London (2025); Auckland Art Gallery Toio Tāmaki, New Zealand (2022), and their touring retrospective exhibition at Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt (2021), Kunsthalle Zurich, Switzerland (2020), Moderna Museet, Stockholm (2019), Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo (2019), and LUMA, Arles, France (2018). Other solo exhibitions include Casa Rusca Museum, Locarno (2020); Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (2019); Helsinki Art Museum, Finland (2018); Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, Australia (2015); The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2015); Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Málaga, Spain touring to Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb (2010); Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania (2008); Tate Modern, London touring to Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany, Castello di Rivoli, Turin, Italy, De Young Museum, San Francisco, California, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York and Milwaukee Art Museum, Wisconsin (2007–08); Serpentine Gallery, London (2002); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1996); Milwaukee Art Museum, Wisconsin touring to The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1985); and Whitechapel Gallery, London touring to Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam and Kunstverein Düsseldorf, Germany (1971). They have participated in numerous group exhibitions including ICA, Miami (2018); HangarBicocca, Milan (2017); The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2011); Barbican Art Gallery, London (2007); 51st Venice Biennale (2005); 5th Biennale de Lyon, France (2000); Carnegie International (1985); and Turner Prize, Tate Gallery, London (1984). In spring 2023, the Gilbert & George Centre in Spitalfields, East London, opened to the public.