Mirosław Bałka’s work, wrought from humble, often elegiac materials, speaks of loss, trauma and alienation, employing the very simplest of means and a lightness of touch. Shaped by personal memory, intergenerational narrative and collective histories surrounding the events of World War II and its aftermath, Bałka creates nuanced works of haunting solemnity. As the artist says: ‘Every day I walk in the paths of the past.’

Born in Warsaw in 1958, Bałka was brought up Catholic in post-war communist Poland. Graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 1985, his early work – including Remembrance of the First Holy Communion (1985) and Angel (1988) – draws on his formative experiences of religious ritual and iconography, treating the figure as an apparition, a proxy for an unclaimable past. In the 1990s, Bałka eschewed representation, developing a visual language whose economy of means and recourse to unusual materials aligned with minimalism and arte povera.

‘After some time’, Bałka recalls, ‘I satisfied my hunger for the form of the human body. I took interest in the forms that accompany the body and in the traces the body leaves: a bed, a coffin, a funeral urn.’ By the late 1990s, only a suggestion of the body remains, either in the hapticity of Bałka’s chosen materials or the specific dimensions of his structures, which often appear as the artwork’s titles. Such titles draw attention to the formal qualities of sculpture, an instance where abstraction cedes to realism. Their sober exactitude apprehends the object in space yet, where the body is concerned, dimensions serve to foreclose the sentimentality so often associated with it. In 250 x 120 x 194, 250 x 120 x 194 (1995), for example, 250 centimetres corresponds to the artist’s height with arms outstretched, an absurd if not harrowing reduction of the body to the quantifiable.

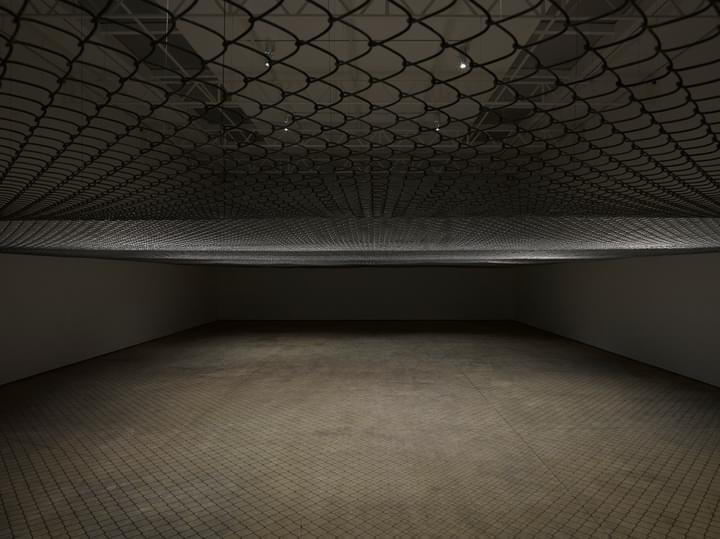

The title of the artist’s major Tate Turbine Hall commission, How It Is (2009), derives from Samuel Beckett’s novel of the same name, in which a lone narrator crawls through mud and darkness. Comprising a 30-metre-long by 13-metre-high enclosure that visitors access via a ramp, Bałka’s sculpture unmoors the senses to incite a primal response: darkness as locus of the unconscious, of fear, of death. The unspeakable tragedies of war surface through association, with the imposing architecture of Balka’s metal container recalling the trains by which Jews were transported to camps and ghettos. Coalescing an increasingly distant yet eerily present horror, How It Is alludes to what the late Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman referred to as ‘another cruelty […] circumscribed by the limits imposed by the intractable foreignness of the past.’

The interplay of light and darkness recurs in other works of Bałka’s. 196 x 230 x 141 (2007) involves a short, steel- and wood-clad corridor with a single illuminated lightbulb drawing the viewer to its centre. As the viewer enters the structure, a motion sensor extinguishes the light, as if a trap ensnaring its occupant. Engaging in the metaphysics of darkness, Bałka has described his practice as an interminable process of ‘digging in the shadows’. This metaphor is nowhere more apparent than in Dlaczego w tej piwnicy (2007), a video work in which the artist repeatedly calls into the void of an open trapdoor at his grandparents’ house: ‘Why didn’t you hide any Jews in this cellar?’

Bałka’s reckoning with inherited history led him to work directly within the landscapes of trauma of his homeland. Asking himself, ‘What do I do for the ones who lived here and are gone?’, works produced in the early 2000s engage with the sites of former internment and extermination camps: Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau. The video work Winterreise (Bambi, Bambi, Pond) (2003), for example, sees deer moving freely across the snow-covered grounds of Auschwitz, their quiet presence and unawareness producing dissonance with the persisting knowledge of past violence and its unassimilable residue. The video work T. Turn (2004), meanwhile, considers disorientation and time by capturing a nauseating 360-degree skyward rotation at the site of Treblinka.

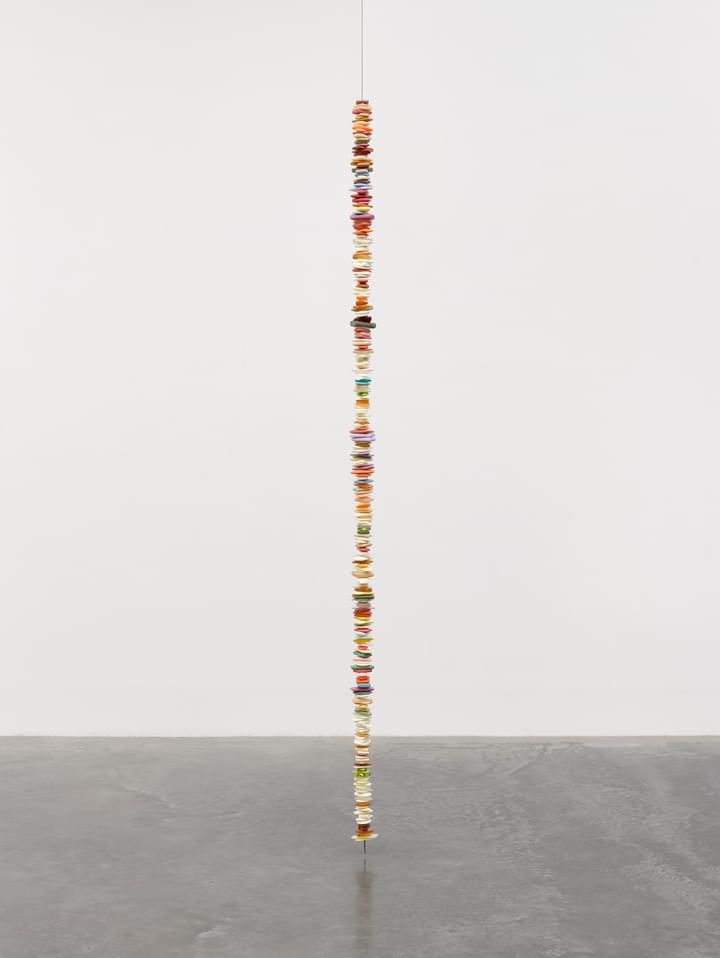

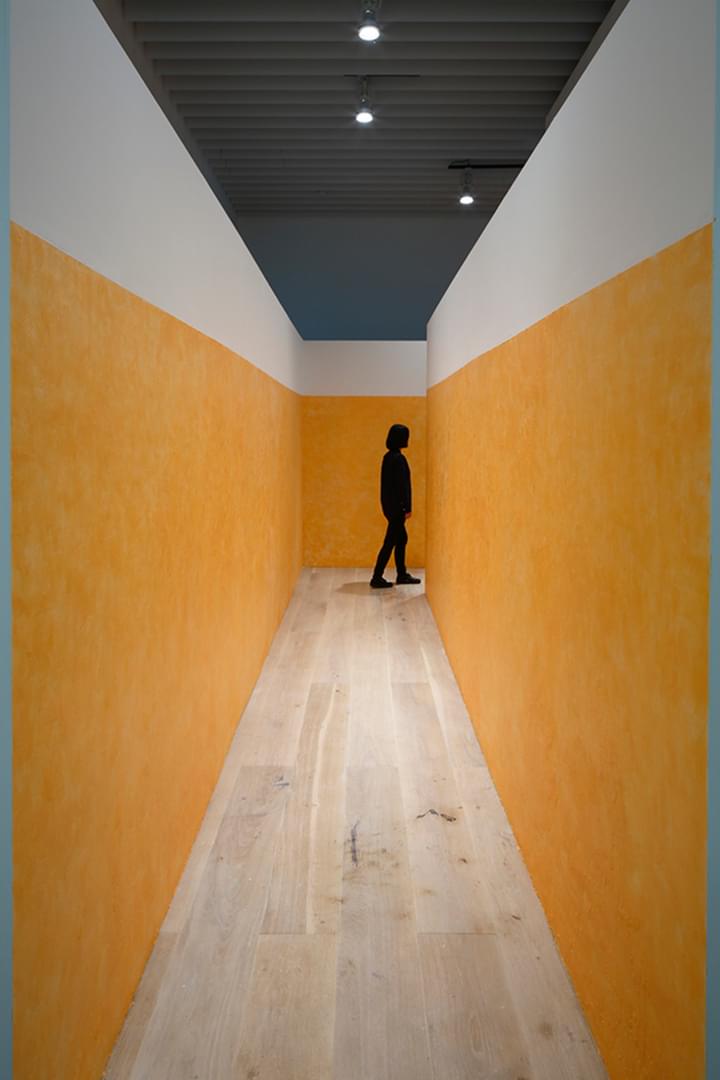

Remarking that the past exists in ‘everything that I can touch’, Bałka often employs objects and materials drawn from his immediate surroundings, including his family home in Otwock, Poland, which has served as his studio since 1992. Simple building materials – wood, linoleum, steel, plaster – are deployed for austere structures within which an experience is framed, while the recurrence of ash, salt and soap freights his artwork with symbolic significance. In 410 x 10 x 10 (2000) and 310 x 9 x 9 (2019), Bałka threads and suspends hundreds of used soap bars from a steel cable, calling to mind the quotidian yet charged ritual of hand-washing and its associations with purification and absolution. The artist’s installation Dead End (2002–04) similarly makes use of a single material metaphor. A corridor with walls coated in ash, Dead End becomes a vessel for the remains of destruction, a poignant memento mori resounding the verse ‘ashes to ashes, dust to dust’. If ash and soap speak to our unyielding fate and the human impulse to resist it, Bałka’s frequent use of salt is equally laden with meaning, ‘associated with memories of the past, dried up tears, dried up sweat, salt on the wounds, and pain.’

More recently, against a backdrop of political unrest – from forced displacement to tightening borders and the ongoing migrant crisis – Bałka realised Random Access Memory (2019), an ambitious installation spanning both floors of White Cube Mason’s Yard, London. In it, corrugated metal sheets block access to the full length of each gallery, delimiting what can be seen to amplify what can be felt: a palpable warmth that emanates as if from behind the wall. Maintained at 45 degrees Celsius – the temperature at which blood coagulates and enzymes denature – the work at once presences the human body and entreats visitors to consider the fine line between comfort and danger. Building upon a previous work, Touch me / Find me (2013), which sees cables heated to body temperature hidden within the walls of an empty gallery, and whose title is an invitation to sense, the artist points to a politics of visibility while foregrounding the primacy of feeling.