Knoebel’s art is resolutely abstract, and takes Kazimir Malevich’s aesthetic notion of ‘pure perception’ as its point of departure. As the artist states, ‘When I am asked about what I think when I look at a painting, I can only answer that I don’t think at all; I look at it and can only take in the beauty, and I don’t want to see it in relation to anything else. Only what I see, simply because it has its own validity.’ Knoebel’s minimal compositions rely on a strict, pared down vocabulary of forms combined with a subtle but commanding use of colour, all of which serves to expose the physical possibilities inherent in the most basic of materials, such as plywood, aluminium and fibreboard. This is best exemplified by the major installation Raum 19 (1968), conceived while Knoebel was still a student under Joseph Beuys, and now part of Dia Beacon’s permanent collection. Borrowing its title from the number of his studio at the Kunstakademie, Raum 19 consists of 184 wood and fibreboard forms such as frames or stretchers, cylinders, cubes and rectangles – a mutable ensemble which can be reconfigured in any number of ways in accordance with the artist’s impulses. While Raum 19 is an expressive constellation that appears to autobiographically refer to an art student’s raw material, the installation is itself an instance of reduction, a formal exercise of peeling back the work of art to its most basic component parts.

Knoebel first began making paintings in the 1960s with the basic organising principle of thick or thin vertical lines drawn at variable distances from each other. Between 1966 and 1973 he produced around 250,000 A4 drawings in pencil line, which he exhibited in six high and narrow steel cupboards, hermetically sealed and accessible only on demand. Fascinated with the conceptual exercise of dematerialising the medium of painting, Knoebel produced numerous works wherein lines or rectilinear shapes were simply projected onto internal or external walls of buildings. This radical approach to painting eventually became a series of black and white abstract works that played with combinations of rectangular forms. Since the mid-1970s, and especially following the death of his friend Blinky Palermo, Knoebel began to systematically experiment with colour, the expansive painting series 24 Farben – für Blinky (1977) marking the beginning of this process. During the 1980s, he started incorporating found objects into his installations; the installation Eigentum Himmelreich (1983) dedicated to Giese (1942–74) is one such example and comprises 17 separate objects including sculptures made of used wood, reliefs, painted wall panels and framed drawings.

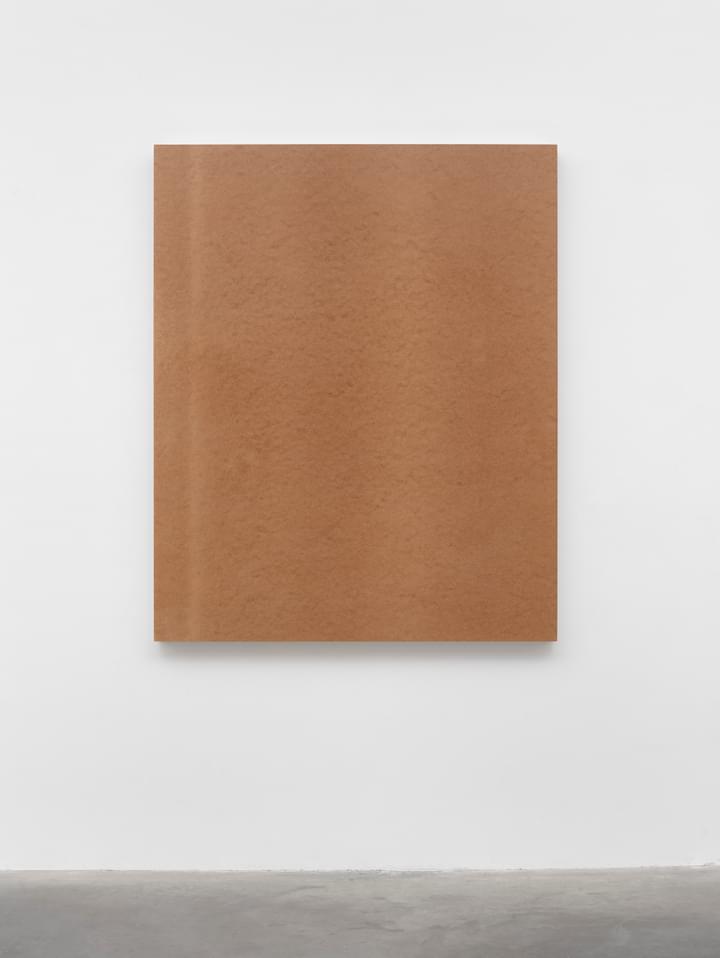

Issuing forth a tension between the material and immaterial, certain of Knoebel’s works make use of visibility and concealment to further this perceptual engagement. The white ‘Drachen’ series begun in 1971, for example, involve scarcely readable quadrilateral works, installed high on the wall to invoke floating. In the plywood ‘sandwich’ paintings, he extends the form of a two-dimensional painting into three-dimensional space by painting one side and joining the panels together, colour side faced inwards. With only a trace of the colour existing in the paint residue gathered around the edges of the work, these paintings enact a pictorial denial, relying solely on the viewer’s projection and literal internalisation of the painting to render the artistic encounter.

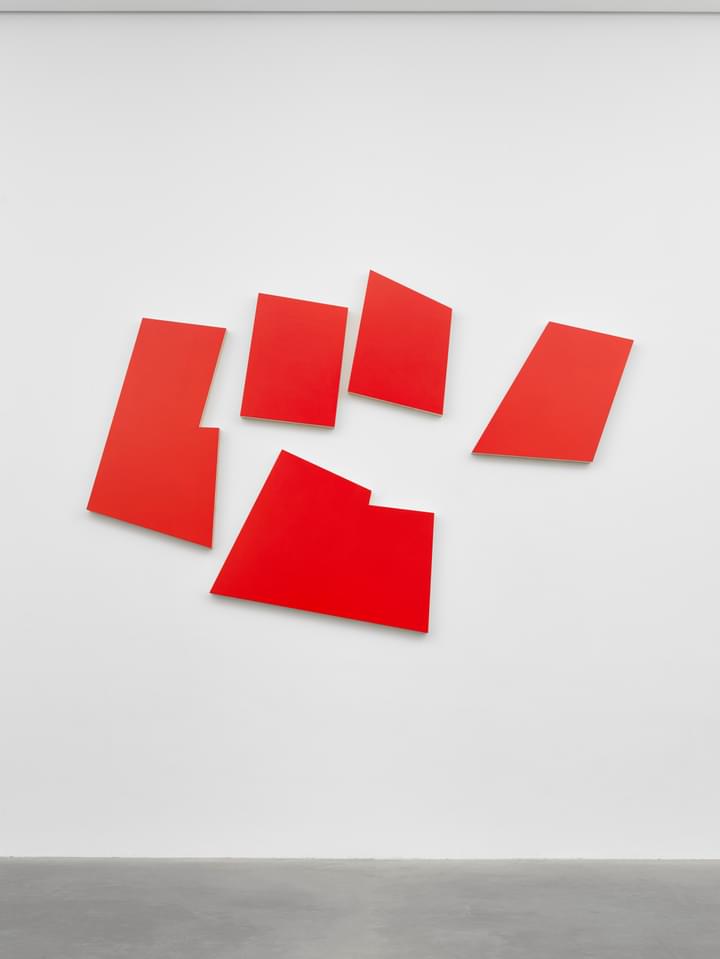

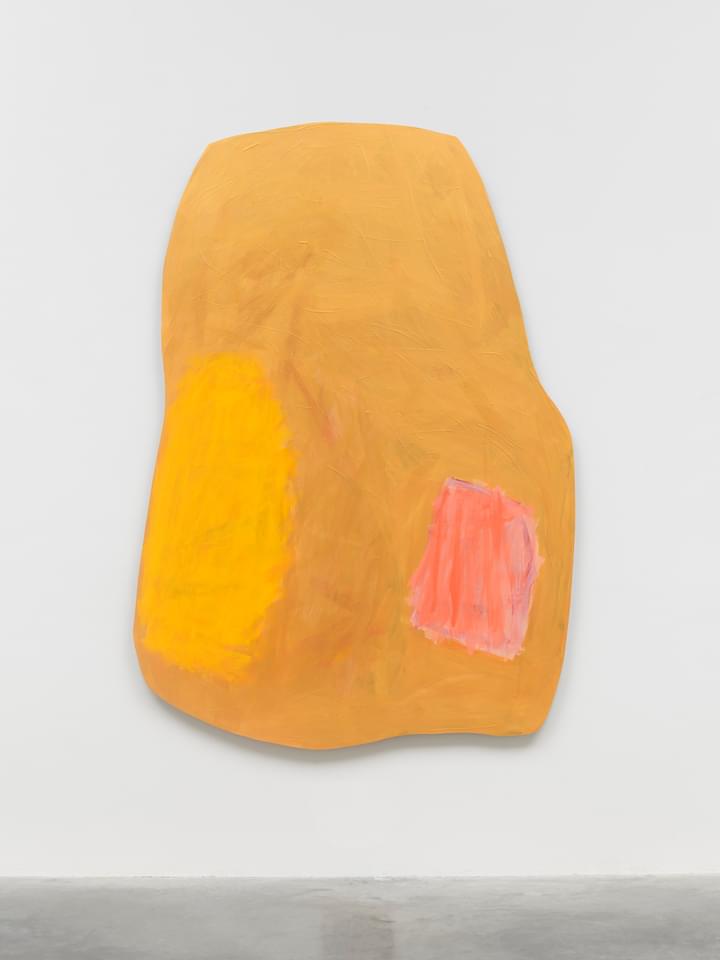

Since the 1990s, Knoebel has used cut-out sheet aluminium as a painting support, as can be seen in ‘Ich Nicht’ (2005–08), a response to Barnett Newman’s series and titular question ‘Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue’ (1966–70). In more recent works, such as the enigmatic Bild 15.10.2019 (2019), Knoebel explores formal juxtapositions – the uninflected hard-edged meeting with feather-stroked gesture, to intriguing, visceral effect. Demonstrating a persisting interest in the architectural since Raum 19, Knoebel has at times incorporated window-like forms or door-shaped sections of wood into recent compositions, as well as sections of mirror that serve to bring the surrounding gallery into their pictorial field. In Ort-Rosa (2013), painting is actively extended to architectural realms, with large panels of pink-painted aluminium joined together to form a room-like space, inviting the viewer to enter an arena of resonant colour. As though iterating upon Ort-Rosa, the artist’s new installation Unterm Strich (2019) again makes use of pink-painted aluminium panels, although this time to cordon off space. Concealed behind this makeshift walling are wooden boxes, trunks of fir trees in dedication to Beuys, and other objects of personal significance referring to touchstone moments in Knoebel’s artistic career.

One of his most notable achievements is the major commission of nine large, stained-glass windows for the royal cathedral of Notre-Dame in Reims installed in 2011 and 2015, which refer to both Matisse’s large-scale installations with paper cut-outs and to the artist’s signature ‘Messerschnitte’, or ‘knife cuts’. The commissioning of these majestic windows – illuminating abstract compositions with hundreds of pieces of glass in vivid shades of red, blue and yellow – carries within it a reconciliatory gesture, since the original stained-glass was lost when the building was badly damaged by German bombing in August 1914.

Imi Knoebel was born in Dessau, Germany, in 1940 and lives and works in Düsseldorf. He has exhibited extensively including solo exhibitions at Museum Haus Konstrucktiv, Zurich, Switzerland (2018); Museum Haus Lange und Haus Esters, Krefeld, Germany (2015); Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, K21, Düsseldorf, Germany (2015); Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany (2014); Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig, Germany (2011); Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (2010); Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin (2009); Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin (2009); Dia:Beacon, New York (2008); Hamburger Kunsthalle, Germany (2004); Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover, Germany (2002); Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, Valencia, Spain (1997); Kunstmuseum Luzern, Switzerland (1997); Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany (1996); and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1996).